Outside Business

The backpack industry's internal framework.

– But...I can't see it from here! –

The backpack industry doesn't really exist, in case you decide to go looking for it. It is part of the outdoor products industry. Maybe you prefer to call it the Recreational Products Industry, or just Leisure Biz. Anyway, it's all part of the same corporate mega-structure.

This mega-structure is worth more than you and all of your relatives, and your friends and their relatives, and their pets, and their pet toys too. This is big business. Not as big as the arms industry, though the two do overlap, and share some basic attitudes. But it is still big. The word industry provides a clue, doesn't it?

So let's capitalize and italicize while we're at it. The Industry.

The Industry has associations and conventions and trade shows. If you are invited to any of them you will be initiated into the mystic rites and learn the sacred handshake and get a secret code whistle, but then you won't be allowed to go home again until you swear a vow of silence. This is all hearsay of course. No one who is privy to the real inner secrets is allowed to talk about them, and live. For long.

Because they mean business. The Industry does.

You've heard of some, some of the big guns — ArcTeryx, Bergans, Black Diamond, Burton, Deuter, Granite Gear, Gregory, JanSport, Kelty, Lowe Alpine, Macpac, Marmot, Mont-Bell, Mountain Hardwear, Mountainsmith, Osprey, Outdoor Research, REI, The North Face, Vaude, Wild Things.

And some of the lesser guns, who tend to appear and vanish with the seasons — CiloGear, Fanatic Fringe, GossamerGear, LuxuryLite Modular, Moonbow Gear, Mountain Laurel Designs, Six Moon Designs, Ultralight Adventure Equipment, Wingnut, ZPacks. But you don't know what goes on behind the Cordura curtain.

Because you can't.

Because it's business.

And they mean business. And business is mean.

Which means you don't get to know, even if you ask politely.

– X marks the pack. –

To give you some idea of how little you actually know about these familiar names (the big ones a few lines back), consider this, from one of the real manufacturers (we'll call them X), located in a stupendously large and well known Asian country teeming with happy and industrious people. The following is an exact quote from them (except for the company name):

X Industry Co., Ltd. was established in 1970 for bags manufacturing industry which is professional in producing bags. It has an area of 2,500 square meters, 150 facilities, 200 workers, and with matched printing workshop. We are the bag manufacturer to be awarded with ISO 9001:2000 certification. Our principle is to provide our clients with products of reasonable price, high quality and punctual delivery. Since 1989, we have been appointed to produce Disney products, which gives us good credit standing by the high quality. Various styles, delicacy working, good quality, pleasing and practicality, reasonable price, and pure-hearted cooperation, obtain us repute from the clients. In case your company want to give us quotation, welcome you contact us betimes; we will reply you as soon as possible. We are not the best, but we can do better. We believe a good beginning is the half of success!

"Welcome you contact us betimes. We are not the best, but we can do better." That's your first clue — this is truly not an American company.

A few of the names of the real players are:

• Anhui Garments Import & Export Company Ltd. • Bags & Luggage. • Anhui Technology Import & Export Company, Ltd. • Anjie Solar Energy Company, Ltd. • Artel Manufacturing, Ltd. • Binki (Group) Corporation. • Brummend Enterprises Company, Ltd. • China Riversuny Waterproof Garments & Bag Manufacturing Ltd. • Chuangfuyuan Hardware And Plastic (Shenzhen) Company, Ltd. • Eliza Industrial Company Ltd. • Fengye Group Company, Ltd. • First Plus (Ningbo) Foreign Trade Company, Ltd. • Fuzhou Baige Bag Manufacturing Company, Ltd. • Fuzhou Hunter Bags & Luggage Manufacturing Company, Ltd. • Fuzhou Oceanal Star Bags Company, Ltd. • Gem Fastival Ltd. • Good Decision International Ltd. • Green Energy Technology Company, Ltd. • Guangzhou V-Goal Handbag Company, Ltd. • H.P Solar Company, Ltd. • Handfa Industrial Company. • Hopemax Industries Company. • Jing Jin Travelling Bags Manufacturing Ltd. • Kingsco Products Company, Ltd. • Kwan Kin Handbag Manufacturing Ltd. • Lap Shun Manufacture Company, Ltd. • Lexon Bags & Accessories Company, Ltd. • Million Time Industrial Ltd. • Ningbo Besli Industrial &Trading Company, Ltd. • Ningbo Bright Company, Ltd. • Ningbo Hi-sun Industry Corporation Ltd. • Ningbo Top Green Enterprises Company, Ltd. • North Peak Trading Company, Ltd. • Pinghu Haomai Industy Ltd. • Quanzhou Haiheng Sports & Tour Goods Company, Ltd. • Quanzhou Jiangnan Handbag Factory. • Quanzhou ShanLiang Bags & Shoes Company, Ltd. • Quanzhou Xinheng Outdoor Equipment Company Ltd. • Real Success Trading Ltd. • Rongchuang Handbag & Clothing Factory. • Shanghai DPS International Trade Company, Ltd. • Shanghai Fine Trading International Ltd. • Shanghai Oumao International Company, Ltd. • Shanghai Paloon Company, Ltd. • Shanghai Well-Signed International Trade Company. • Ltd. • Shenzhen Saintmart Crafts & Premiums Company, Ltd. • Topbo Industrial Ltd. • Tung Hsien Luggage Company, Ltd. • Uni-Ray (China) Ltd. • Unison Light Industrial Manufacturing Company, Ltd. • Waterpride Enterprise Company, Ltd. • Winfung Worldwide Enterprises, Ltd. • X & M Bagson Company, Ltd. • Xiamen B&G Company, Ltd. • Xiamen Bestwinn Import & Export Company, Ltd. • Xiamen Carl Import & Export Company, LTD. • Xiamen Daysun Bags Industrial Company, Ltd. • Xiamen Goldenway Enterprises Company, Ltd. • Xiamen International Trade & Industrial Company LTD. • Xiamen Senyang Company, Ltd. • Xiamen Uptex Industrial Company, Ltd. • Yesun Bag Industrial Company, Ltd. • Yiko Bags Manufacturing (H.K.) Ltd. • Ying Kit Handbag Manufacturing Company Ltd. • Yiwu Unique Bags & Cases Company, Ltd. • Yongchang Industries Company, Ltd. • Zhumadian City Kangmao Arts & Crafts Company, Ltd.

As stated, these are a few of the names. Only a few. There are hundreds more, but they share one characteristic — they are all after your money.

Even the Binki Group.

– The real Mountain Outdoor Hardware Jan Gear. –

The next time you buy a new pack bearing the colorful and distinctive Mountain Outdoor Hardware Jan Gear label, remember that you may be buying a pack actually made by the Xiamen Tung Ningbo Jing Jin Foreign Trade Company. And the pack may be great. It may be made by a different company than the next pack in the bin, even if they look identical and bear exactly the same label and price tag. And that probably won't matter at all.

Because the Xiamen Tung Ningbo Jing Jin Foreign Trade Company "believes the fundamental function of management is to inspire employees with sincerity and affection, establish a relaxing and autonomous environment to create value efficiently," through "fierce competition" which "enables service to be the biggest add-on value source." Because "profound R&D capability, reliable manufacturing process control, outstanding service system and solid team spirit make Xiamen Tung Ningbo Jing Jin Foreign Trade Company products upgrade regularly and receive warm welcome home and abroad."

And that's what you, as a consuming organism really want, isn't it?

Isn't it?

We don't hear you breathing...don't forget to take a breath now.

Try it.

Breathe in.

Breathe out.

Relax. Do not become overwhelmed. Not to worry about details, sir or madam. Your needs are being efficiently met by friendly background processes. Which came from somewhere, but where?

– 20,000 years of quality and counting. –

Remember Frozen Fritz? Or Ötzi the Iceman, as he is officially known (by those who have never actually had a beer with him)?

Well, his people started sewing things together as far back as 20,000 years ago, during the last ice age. Who knows for sure if it was absolutely the last ice age, so let's call it one of the more recent ice ages. Archaeologists, clever and observant folk, have discovered bone needles from way back then, and these needles had eyes, and were used to sew together skins and furs way back when. So far no one has determined what the eyes were for or what they saw, but teams of researchers are continuing work on this as we speak.

So, leaping over several thousand years as though they weren't there we skip ahead from Fritz's time into the early Iron Age, around 300 B.C.E. (Back in the Creepy Era). By that time some forward thinking Celts had somehow developed sewing needles of this stuff (iron, named after the age they found themselves in) and a few of these Celts seem to have absentmindedly dropped some of these needles inside one of their hill forts at what is now Manching, Germany. These same needles were found many, many hundreds of years later by people who had no haystacks to look in, and so had gone seeking needles on German hilltops out of sheer desperation.

Research indicates that the diet of these early people (the Iron Age Celts) was mainly barley and spelt, with some millet, einkorn, emmer, avena, wheat, and rye thrown in whenever they could catch any of it. On good days the sturdy Celts might have had enough additional lentils, beans, nuts, or fruit to make a difference. Considering their diet, they may simply have invented needles in order to poke themselves for amusement rather than for any other purpose. No one likes eating something called spelt, and it, einkorn, emmer, and wheat are pretty much different names for the same boring tasteless whatever.

These are, after all, foods that can be fully described in words of at most two syllables, and none of them has ever gotten more than a one-star recommendation from anyone who matters, at best. And at their best they taste like clinical depression, though chewier, on a good day, and contain more weevils, if that helps. If you get one of the better brands, of which there are none.

Whenever possible, those people (the Iron Age Celts again) also caught, killed, hacked apart, and ate anything that looked remotely like meat, possibly to help relieve the unendurable annoyance of endlessly poking themselves with needles for amusement. No one knows what the hell Celts were doing mucking around in Germany either. What was that about then, back in the Creepy Era?

All of this seems suspiciously out of character. Especially since the rest of the Celtic clan, the ones we actually are familiar with, have stubbornly hung out in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and England (as a last resort), spending their days drinking in pubs, tormenting various kinds of bagpipes, tootling on tin whistles, and clomping around feverishly in what they insist is a kind of dancing. Between brawls.

Go figure.

Nevertheless, the discovery of ancient needles in Germany sent Chinese archaeologists straight into a howling patriotic snit, enough of a snit to force them to fan out across the landscape, furiously digging up endless reaches of it until after years and years they finally came across a Han Dynasty tomb dating from somewhere around 202 B.C.E to 220 A.D. (After Daybreak). They reported finding a complete sewing set, including even a thimble. Take that, Celts.

Technology — it's out there.

– The rise of the machines. –

In 1790 (as we blithely skip another 1500 years) the first passable sewing machine was patented by British inventor Thomas Saint. Fancying himself an adept at marketing, Saint titled his patent An Entire New Method of Making and Completing Shoes, Boots, Splatterdashes, Clogs, and Other Articles, by Means of Tools and Machines also Invented by Me for that Purpose, and of Certain Compositions of the Nature of Japan or Varnish, which will be very advantageous in many useful Appliances.

This patent contains descriptions of random varnish concoctions and at least three different machines, only one of which was for stitching, quilting, or sewing. Obviously Saint couldn't make up his mind about what he was up to, and so, with a level of enthusiasm equal to Saint's level of clarity, the rest of the world delightedly ignored him and his ideas, and Saint's whole workshop full of prototype gizmos and thingamabobs vanished like a crab apple dropped down the sit hole of a pit toilet. Silently, beyond reach, and forever.

For the following 83 years, the nearest thing to a commercially-successful sewing machine was only a hazy dream.

Though much, much later (well into the Plastic Era, or Modern Times as we see it from inside our smug, cozy iBubble) someone pried the idea of Saint's sewing machine from history's dung heap, built a model, tweaked the model a bit, and got it working. So maybe Saint wasn't inept, but devious (as are many of the British persuasion, we are told), and had deliberately obfuscated his patent description, to prevent anyone from copying his invention.

At least he got the mechanical part right, but overall, nothing came of Saint's work. Marketing in secret, how smart was that?

Ladies and gentlemen — On to France!

– The era of raging French tailors. –

In 1830 a Frenchman named Barthelemy Thimonnier invented the first really functional sewing machine for use in his garment factory, but he almost went nuts trying to get it working. It happens.

See, the deal was that many of the people where he lived were weavers.

Thimonnier had a personal moment of awakening when he first thought things through, and then — an inspiration, to him she came!

Thimonnier noticed that weaving was really quick compared to sewing fabric that came off the looms. By his time weaving had been fully mechanized, but sewing remained a handicraft. Catch the drift?

Thimonnier decided his mission in life was to invent a machine to do for sewing what programmable Jacquard looms had done for weaving. But inventing a machine that sewed turned out to be even harder than the sewing. Machines were hard to invent back then. Tons of that clunky iron stuff had to be cast, and hammered endlessly, and the wheels and pulleys all over, and those decorative whirling doodads, all of which, it seems, were required by law or royal edict or something. Something. It was hard.

Anyway, Thimonnier was the man for the job, he thought.

So he holed himself up in a shed and worked like a madman for years and years and years (in secret) before he got his machine working. His neighbors thought he was spooky, and not in an agreeable way. He may have been spooky. He probably was spooky, and possibly very spooky. Imagine what kind of shape you would get into, locked in a shed for years, tinkering until your tinker began to bleed. And then continuing to tinker, and so on, day after day, year after year, until your tinker eventually became calloused and almost unrecognizable.

Eventually though, Thimonnier did it (i.e., he finished the inventing part), and by 1841 he had 80 machines whirring along in his factory, churning out uniforms like crazy for the French army.

But wait. There's more! Rampaging tailors!

Those who made their living by sewing got nervous about Thimonnier's factory, and then they got angry, and so a mob of them sort of decided to storm the place one night — being French, and angry, and all. Anyway, it seemed like a really good idea at the time. And it was, because they destroyed everything, completely and totally.

Thimonnier tried to start over, but the tailors were watching from the bushes. They regrouped and struck a second time, once again destroying everything.

This kind of muscular rabid persistence is not something you see too often among tailors, but things were tough in France about then. People were rioting all over for all kinds reasons. It was the thing to do, and who were they to buck the system? Thimonnier had to bail, and escaped to England with his last, lone surviving machine, but England was not a great business move either. Thimonnier only managed to die there, in poverty. See? Not a great business move. Death was his big slip-up, and after that things only decayed further.

Score one for tradition, zero for Barthelemy T.

If you think the idea of rioting French tailors is funny then keep in mind who invented sabotage.

Yep — da French.

One version (mythical) is that a bit before Thimonnier's time, workers in fabric mills, upset by the idea of power looms putting them out of work, threw their wooden shoes (sabots) into the looms. This makes a tidy story about how the wooden shoes then clogged the looms to death.

But it's more likely that the first sabotage actually happened much later, during a 1910 railway strike, when workers destroyed the wooden shoes (sabots, or what we call ties) that anchored the rails, thereby disrupting transport long enough to create a major kerfuffle. It worked. Get the wrong people mad enough and they can do anything. Even tailors. (Tip — one thing you absolutely do not want to see coming at you is raving, raging librarians. Or Quakers foaming at the mouth and screaming obscenities. Nope. Once you have howling Quakers (or librarians) waving clubs or poking pitchforks in your direction, you have very little hope of ever again sitting down to a quiet supper with the cat.)

So.

– Enter Elias, the loser. –

Time marches on. There were still no backpacks for sale, but sewing machines inched closer to reality, and they had to come before machine-sewn backpacks, so...

Switch to America. Yay!

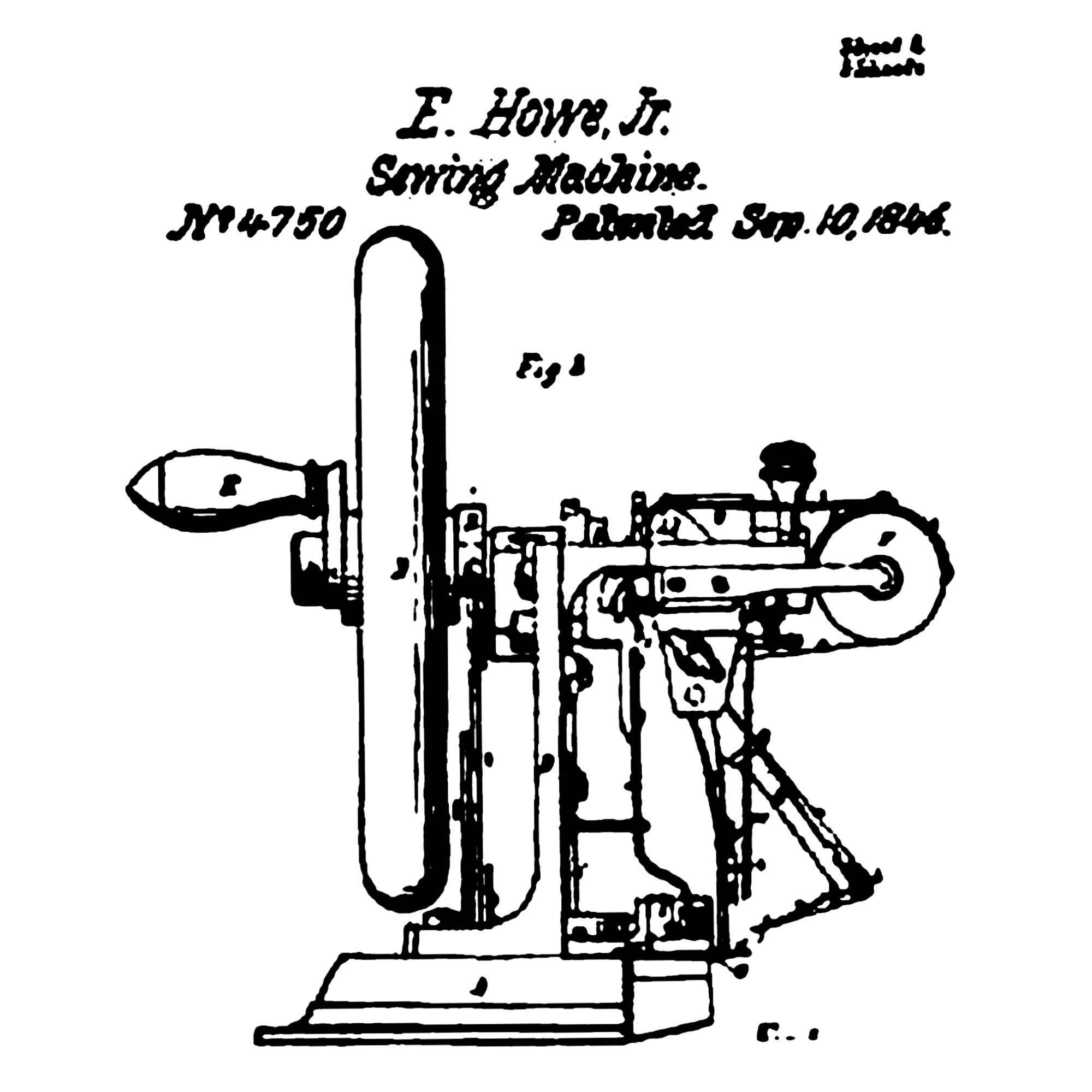

On July 9, 1819, in Spencer, Massachusetts, a loser was born. His name was Elias Howe and he was the inventor of the first American-patented sewing machine.

Eventually Elias Howe became one of the richest men on earth, which is pretty good for a loser. But Elias Howe was a loser first, and for a long, long time, and he won the game only much later, in the last moments of the final inning, almost by accident. It was a squeaker for old Elias. A close one.

OK then, here's the story.

First, the young Elias Howe lost a factory job he had, but snagged a new one as a machinist. He soon took sick though, lost that job, and spent long, long days watching his wife support him by taking in sewing. This may have been his inspiration, though some say he started tinkering earlier, back during his machine shop days. However it went, we do know for sure that Elias Howe was another man who got his tinker on, and after getting a taste of that, was unable to quit.

Anyway, after enough thinking and puttering and poking and tinkering, Howe finally, somehow, invented the first two-thread, lock stitch sewing machine. That does have a nice ring. Two-thread. Lock stitch. Sewing machine. All American. Yay again.

Previous machines, the ones that worked at all, used a chain stitch, which is sloppy and can be unraveled if cut, which is the point of it. This stitch is still used, and is handy for things like bags of flour that need to be opened easily for dumping. Grab the correct loose thread, pull, and it all unzips. Pull, unzip, dump. Pull, unzip, dump. Etc. (Go ahead and check this out if you buy dog or cat food in one of those heavy paper bags that is sewn shut. Twiddle a bit, and you'll be able to unzip it rather than cutting it open — very elegant.)

But another stitch, the lock stitch, is better for most things, like, say, clothes. Because the stitch locks. Because it is a stitch that, once stitched, stays that way. Because the stitch locks. Get it? Clever. The lock stitch helps you keep your pants on without that constant nagging worry about having the seams all let go the next time you brush against some grumpy shrubbery.

Besides the lock stitch, Howe's sewing machine had other improvements to brag about.

For example, the needle had a hole at the pointy end, not the other one. This hole at the pointy end allowed the needle to push thread through the fabric so that the thread could be locked in place on the back side of the fabric as the needle pulled back out, which made the lock stitch possible in the first place.

Once Howe got his machine right, he patented it on September 10, 1846 in New Hartford, Connecticut, but it was clunky and awkward and not a big seller, mainly because Elias Howe was a lousy salesman. So he went broke. Dead broke. And remained a loser.

– Loser! And Howe. –

Even after putting his machine up against five fast hand-sewers and blowing the whole group away with an unbeatable 250 stitches per minute, Howe was unable to impress anyone.

Anyone at all.

No one bought Howe's sewing machines.

Does this remind you of Lloyd F. Nelson? The guy who invented the Trapper Nelson pack? Remember him? Anyone? Hellooooooo...

Same deal. No one could imagine why a machine was needed to do something that a crowd of dirt cheap women pulling needles by candlelight while stuffed into the back end of a dark shed could do. It was beyond understanding.

So Howe also went to England, and tried selling machines there for a couple of years. But. Failed there too. Failed. Utterly. He finally gave up and came dragging his tail back home, a total limping failing loser. Broke again.

But guess what?

Bing!

Something had changed.

Once he was back in the U.S. of A. again, Howe saw sewing machines all over, practically under every bush. The place was absolutely, madly hopping with sewing machines, all whirring away madly, everywhere.

Something strange had happened while Howe was in England. Which was that sewing machines had caught on like crazy. (Now do you remember Lloyd F. Nelson?)

There were lots and lots of companies making sewing machines, and they were all pulling in cash hand over fist, basketful after basketful, and exactly every single one of those machines infringed on Howe's 1846 patent. All of them. Every damn one. Without exception.

So guess what he did? He chose the American way, and one by one, Howe sued the other manufacturers into submission.

First, he won.

Then he won again.

And then he won again, and again.

Howe's annual income went from $300 to more than $200,000, and a bit later it hit a lifetime total of more than $2 million, making him, by the time of his death, one of the richest men who had ever lived.

In today's money this is like going from somewhere around $7000 or $8000 a year to $4 or $5 million a year, in one huge insane leap. Think about that. The dollars don't translate exactly between then and now, but you get the picture. In today's dollars, Howe's accumulated lifetime earnings were somewhere in the $28 to $55 million range, depending on which calculator you use. Not many back then had bucks like that. One source claims that Howe was the second wealthiest man in the world when he died in 1867. Which was also the year his patent ran out. And the year he turned 48. Howe had a disappointing, short life, but, in the end, decent timing.

Well Elias, you done it buddy, you done it after all.

There were still no backpacks for sale though.

– So what happened next? –

Hang on — we're getting closer.

Now comes on the scene Elias Howe's partner. You know his name. His last wife (one of many) was regarded as one of the world's most stunning beauties. She is rumored to have been the model for the Statue of Liberty. Some say yes and some say no, but hey.

Good story.

The two of them, this man and his wife, eventually left the U.S. under a huge cloud of scandal over something or other, and went on to build an English palace whose looming doors were large enough to accommodate horse drawn carriages so guests could embark and disembark out of the weather. This man fathered more than two dozen children (no one is sure exactly how many) by various wives, mistresses (lots — more than you have fingers to count them), and flocks of anonymous lovers. He was one of the world's best salesmen, and died one of the world's wealthiest men, richer even than Elias Howe. Much, much richer.

He never went backpacking either. But he helped make it possible.

And his name was...?

Give up?

Isaac Merritt Singer.

Isaac Merritt Singer was his name, and earlier on Elias Howe had sued Singer, and had severely whupped Singer's butt in court, but then they made up, partnered, and got filthy rich together by forming a sewing machine monopoly in cahoots with a few other, smaller manufacturers. Hey, it was business.

They rocked. You, like almost everyone else, have heard of the Singer Sewing Machine Company, even if you can't tell a sewing machine from a rabid mongoose.

This Singer, he was a flamboyant rascal, he. Not at all what you think of when you see a prim sewing machine sitting on your maiden aunt's work table.

Sure, he had violated Howe's patent, but in the process he had also immensely improved the machine as well, and it sold like crazy, so for a while in the early days he could afford to be sued. He was an established inventor in his own right (getting 20 of his own patents), and a man overflowing with natural ingenuity.

Among his sewing machine improvements were:

- a straight vertical needle instead of a curved horizontal one

- power delivered by a foot treadle rather than a hand crank

- a built-in table to support the work

- a presser foot to hold the fabric flat while the needle poked it

- a rigid arm with a moving needle instead of a needle stuck in the end of a vibrating arm

And Singer marketed well. Very well. Exceedingly well. Crazy well. He was a marketing genius, this guy.

Like Howe, Singer had set up contests between his machine and batches of the fastest sewers working in clothing factories. But unlike Howe, Singer created purchase lust. He actually sold machines, which was the point after all.

And.

Singer provided a 12-month guarantee for every single stitch produced by each and every one of his sewing machines. Think about it.

Singer's company had the first million-dollar advertising budget, ever. And a service department. And was the first to sell on the installment plan. That was the kicker, that one. Everyone wanted a sewing machine, but the machines were hellishly expensive then. Hellishly. So Singer let customers pay a few dollars a month, forever.

Deal. People loved that.

The money, first as little trickles, became creeks, then streams, then rivers, until finally the torrent of money raged and roared right into Singer's bank account in a gigantic, thundering, uncountable tsunami of cash.

Born in 1811, Singer died in July 1875 at the age of 64, of heart failure, leaving either one or two wills, 24 to 28 children (or more), and a $13 million to $14 million estate. In today's dollars that would be somewhere between $250 and $270 million. In real terms, it was more like a multi-billion-dollar estate, since the mere numbers don't translate exactly. There was less money around then, and swinging a bag of cash in those days did significantly more damage.

After Singer's death there was furious infighting reported among his heirs and supposed heirs and most everyone else. Imagine. Finally, decades later, Daisy Singer Alexander, the last heir standing, wrote a note reading "To avoid confusion, I leave my entire estate to the lucky person who finds this bottle, and to my attorney, Barry Cohen, share and share alike. Daisy Alexander, June 20, 1937." Then she sealed the note in a bottle and dropped the bottle into the Thames River in London.

Alexander died two years later, in 1939. Her estate was worth $12 million, and the bottled note was her only will.

In 1949, in San Francisco, the unemployed and nearly penniless Jack Wurm (or Jack Wrum, or Jack Worm), walking along a beach, found a bottle with a note in it. The note was Daisy Singer Alexander's will. He got $6 million, and an additional $80,000 a year from the Singer stock that he also inherited.

The bottle is thought to have traveled to the North Sea, to Scandinavia, then past Russia and Siberia, through the Bering Straits and into the Pacific Ocean, where it drifted south until finally, after twelve years, it bumped into a San Francisco beach. True, maybe. Aren't good stories always true?

And so, with everyone safely dead, everything settled, and after all these years of struggle, the sewing machine was finally on the scene, and it became possible to manufacture backpacks commercially.

The only remaining hitch was finding some decent fabric.2, 3

– Footsie Notes –

1: Background on sewing machines: http://bit.ly/1A9uHCU

2: More background on sewing machines: http://bit.ly/1sg0zl7