Story Break

The Civil War Life.

Billy Yank's Observations.

Upon my enrollment in the Army I quickly learned how to manage my life in the field. It takes time but little else, other than a bit of observation, and some small level of Persistence, if you possess any wits at all, for it does require but a minimum of wits, and though they may be but the slow kind, yet they may suffice.

Since I am still among you, that must be my situation then. I must be both alive and continuing to manage my affairs or I should not be writing any of these words. Tomorrow may be different, but it shall have to be its own lookout.

You arrive in the Army young and dumb and if you are lucky you may become old, and perhaps not quite so dumb. Some things become easier in the meanwhile.

Firstly, you must take what they give you. There is no choice. There is over-much of what you are given, and you are also over-burdened, but nevertheless you do preserve the choice of what to keep and what to discard, and so you soon learn to vigorously exercise choice in whatever arenas as you may.

Each recruit when he begins has new clothes, a new hat, new shoes, trimmings on his shirt front, letters and crossed-guns on his hat, a new knife for all the more ragged fellows to borrow, a nice comb to use, a little glass to shave by, smoking tobacco, and money in his pocket to be lent out. A great convenience he thusly proves to his new mates, some of whom have become the worse for wear in the meantime, though always happy to find a fresh friend with clean new things and money to share around.

He, the new recruit, is a godsend for his mates, the more senior they, and veterans all, for not only has he so many things that they may borrow, but he also proves eager to go on guard, to get wet, to give away his rations, to bring water, and cut wood, and tend to the horses, and he arrives so well-scrubbed and fresh, with cheeks so rosy that all the fellows are glad to see him for the value of his amusing appearance alone if for no other reason.

And of course it is interesting to hear him talk, this new recruit, for he comes possessed of great knowledge of war, of arms, tents, knapsacks, ammunition, marching, fighting, camping, cooking, shooting, and everything a soldier is and does. It is remarkable how much a fresh young recruit and how little an old bedraggled, weary soldier knows of such things. But then, after a while, the recruit forgets in his turn all he knows, and after some days or weeks or months, if he survives, he becomes as ignorant as any veteran. That was true of me as well. I was all too bright and shiny once, and had grand aspirations, now long abandoned.

Firstly, we had our wool uniforms, all blue, with a black belt upon which to carry the cartridge box, cap box, bayonet, and scabbard, and then a canteen and a tin plate, cup, knife, fork and spoon, some of which hung from this belt as well, and some of which were secreted in either knapsack or bed roll, depending upon one's personal inclinations. A skillet too was possibly carried, but we soon learned some tricks there, either by banding together to cook as a group, using but one and the same pan in succession, each for his own cooking, or better yet, as some did, applying a dram of powder to the inside of a metal canteen and touching it off, the concussion sundering said vessel in twain along its seams, thereby providing, among the two halves, both a small pan for frying and a plate for eating, and saving the weight of a skillet altogether.

As to the uniform, as noted, ours were wool, which proved a blessing in winter and a curse in summer yet we were manifestly obliged to keep to this dress despite all good sense to the contrary, though many could and did somehow manage a cotton blouse, sent from home. Were it possible I would have done so as well but luck was not with me and so I had to live with the constant itch and stink of wool though its quality I must say was fair, if not its coolness or comfort in summer.

And we had quite a time with our uniforms overall, as fit was but a matter only of chance.

I, being of average height and girth, generally came out nearly satisfied, if that word may be used, but many of my taller and more lanky brethren saw their wrists and ankles extend well beyond their cuffs and yet those who stood very much shorter than the average flopped about like children in their fathers' suits. There was much trading around till each could get as close a fit as might be, but some were never well served at all, and this added a goodly measure to their suffering. And many among us, and I swear this was so, upon the grave of my grandmother, when issued drawers, knew not what they were, never having seen them before, let alone worn same, and were endlessly confounded by them. I swear, 'tis the truth, and resulted in much hilarity among some of us, and, you may be sure, some anger too among those who were the butt of our jests.

We all began to think of these, presently then, upon due reflection, as the absolute minimum: a Gun, a Knapsack, a Canteen, a tin Cup, and a Haversack. Most wore linen gaiters besides.

In our Knapsacks at the outset we carried a fatigue jacket, several pair of white gloves, several pair of drawers, several white shirts. Then undershirts, linen collars, neckties, a white vest, socks, and etc., filling our knapsacks in the end to overflowing. Strapped on the outside of same were one or two blankets, an oilcloth or gum poncho, and extra shoes. Most of the knapsacks weighed between thirty and forty pounds, but some were so full that they weighed beyond fifty, if you may believe that! And since we as enlisted were required to carry all upon our bodies, unlike the officers, we soon pared back to the absolute essentials only, by discarding much, either openly or on the sly, as circumstances allowed.

As for food, we received a variety, or were due it at any rate, though the truth was all too often distant from the promise. Meat and bread were our staples, and glad of them we were, the standard issue being three days' worth when in the field, to be carried by each as he went.

Fresh beef, when disbursed, was always a favorite though salt pork proved more common, or salted beef. We often fried our meat, though any form of cooking possible was applied, including broiling and boiling, and many a bayonet was pressed into service as a cooking-spit.

When possessed of some degree of luck we had also rice, peas, beans, dried apples, dried peaches, potatoes, molasses, vinegar, and salt, though we would not have rice had we beans or peas, or the other way about, and so it was. As well there might be a brick of desiccated vegetables, with coffee, tea, sugar, candles, soap, pepper, and salt, but many of these were all too rarely seen.

As a general rule the marching rations were as follows for each soldier:

- Of meat, 12 ounces Salt Pork or Bacon, or if not then one pound and four ounces of salted or fresh Beef.

- Of Bread, one pound and six ounces of soft bread or flour, or one pound hard bread (or as we knew it, Hard-Tack), or one pound and four ounces of Corn Meal.

Then for each entire company of one hundred these were issued in addition:

- 10 pounds Coffee,

- 15 pounds Sugar,

- 3 pounds and 12 ounces of Salt.

But even meat, so necessary to assuage hunger and maintain health, was often in short supply, and we relied for the mere continuation of life upon bread, and that which the Army gave to us with great regularity was not soft, well yeasted, and gently baked but was of the variety known as Sheet Iron Cracker, or the tooth-dulling Hard-Tack. Nothing but plain flour and water went into it, and these two ingredients were fired in furnaces until hard as could be, and we had to make do with what issued from that process.

In size each piece of this Hard-Tack measured three and one-eighths by two and seven-eighths inches, and was nearly half an inch thick, as near to iron as may be among things carrying the name food, and sturdy enough to break a tooth on. To each Company these were delivered by weight, but then again re-distributed to us by number, either nine or ten to each man, depending on the rules of the regiment one served in, but there was always plenty for those who wanted more, as some would not even touch these, and though they supplied for our needs, yet eating a whole issue still left a man hungry for the taste of real food, and with aching teeth besides.

Many a musket butt was applied vigorously to such a hard-cake or tack set upon a stone, to provide a bit of softening to it. Some would toast hard-tacks over a fire, crumble them into soups, or fry shards of them with pork and bacon fat as skillygalee, which provided a passable mess, surprisingly. And as often as not, sad to say, these hardtacks were rife with several kinds of blind creeping Pests and vermin, and so among us they earned the name of Worm Castles. How dearly we longed for soft-tack, or real Bread, in loaves, such as we had grown accustomed to at home, but we seldom saw it, seldom indeed.

All rations went into a Haversack Bag, which was intended exclusively for food, having one sling whereby it hung from the shoulder and neck, and some of these boasted an inner liner of cloth, the idea being for the carrier to remove and wash said cloth as exigency demanded and conditions allowed, but even that precaution did not prevent the accumulation of grease and foul odors and yet additional crawling things following upon weeks of use. Lacking such a liner supplied at the manufactory a man could if he wished sew up a small draw string bag or Pouch, therewith to wrap his rations for storage, or at least, if not that, possibly lacking in sewing apparatus or skills he could find a few rags from an old shirt to serve this purpose.

The Haversack as noted was a bag, but a simple bag slung round the neck, yet rigid enough somehow to maintain its shape, the strap going over one shoulder, and though the styles of these bags varied from one model to another, one being plain, of undyed cotton, another dyed dark, yet another painted or striped, still they were all plainly close relatives.

But Knapsacks, our other form of duffel, were more various in their styles. These devices were intended as the soldier's most important equipage after weapons, being the repository of each and every Thing that made a soldier a human being rather than a simple Beast or roving wild Animal of the fields. The knapsack held every personal item a soldier might own such as a woollen blanket, India rubber blanket, tent half, shirt and socks, and so on, and his personal Effects besides.

A change of flannels may have been included, for those who knew the use of them, and the manner of such use was this, learned by trial and error: the experienced campaigner when the time came discarded those flannels he had on, donned a clean set, and if he had access to another clean set, or could acquire one, would retain them against the future as his next change, and hold them in his knapsack until needed, as laundering was considered a waste of time and effort, and too seldom possible besides, to be depended upon.

In addition there might be such sundries in a Knapsack as a pocket knife, an extra shoe lace, a candle end or two (with matches in a tin container), and a housewife as the soldier calls his Sewing-kit, but not much more, lest it be a Testament or a packet of letters from home, or a bit of writing material and a pencil stub, for those who knew their letters.

Many commonly dropped their packs in a pile before battle, only to suffer bitter regret later upon finding those packs lost forever, whether they were carried off by stragglers, or when an engagement swept a regiment far from their baggage as a surging Wave upon a stream might carry a fleet of twigs and fallen leaves afar, and so they would never see their packs again, or any of their goods at all, or even their most precious keepsakes. Yet some took the devil of a chance and carried their things straight into battle with them, to prevent loss, even at the risk of life. Despite the dearness of a Knapsack's contents, its lightening by the discarding of useless items signaled the first emergence of a hardened fighter. Getting into Light Marching Order was the inevitable necessity.

So, at the beginning, all our knapsacks held over-much. This has been noted already, and it was true.

At the very first halt of our very first march we recruits would suddenly scramble hastily to lighten our loads by discarding anything extra, you may be assured, anything at all superfluous, as a single hour's actual experience would serve to remove the scales from our eyes, and thereby to reveal the truth.

The ground all too suddenly became strewn with blankets, overcoats, dress-coats, pantaloons, shirts — in fact, everything the soldier who had been through the mill would not tolerate keeping for a single moment if it oppressed him in the slightest. But some even, all new recruits of course, and yet but exceedingly few of them, would persist yet a while and cling to each single thing until bent over at the waist, gasping, eyes staring, jaw hanging, and face dripping with sweat. But this lesson was learned in due time by even the slowest, as might be imagined, and they shed their excess as each and every tree in fall sheds its leaves in turn, in order to survive what is about to come their way.

If you were to follow the column after, say, the first two miles, you would find various Articles curiously scattered at intervals along the roadway, where a soldier quietly broke ranks, sat, unslung his knapsack or his blanket-roll, took out what he had decided was too much, and, thus relieved, hastened to rejoin the regiment. It did not require much time for an army to get into light marching order after it was once fairly on the road, as this process in truth happened quite rapidly.

For at every step, no matter how light it had seemed at the first, the Knapsack grew heavier. The soldier's heated, sweating back smarted under the pressure of it. His cartridge-box, with its leaden load, bobbed at every footfall, up and down again and again, chafing and grinding until that spot of his body felt as if it were wedded to a red-hot iron. His canteen and haversack rubbed the skin off his hips, the extra bunches of cartridges in his pockets scraped his legs, and his musket crushed his shoulder like a piece of iron railing.

Those living along the line of march or even near it watched closely, and often followed the moving Army for miles, gathering up whatever the soldiers threw aside. Men, women, children, and even grandmothers from miles around loaded themselves with quilts, clothing, and other articles of every description. This shrinkage of the knapsack was the first symptom of the transformation that saw the raw recruit change into an effective soldier, ready at any moment for either a fight or a footrace.

So then, of these Knapsacks we may say there were of Types, several. The rarest perhaps, used chiefly early in the Conflict, was the Kibler knapsack, an instrument formed of but a single Bag, and having but one Compartment.

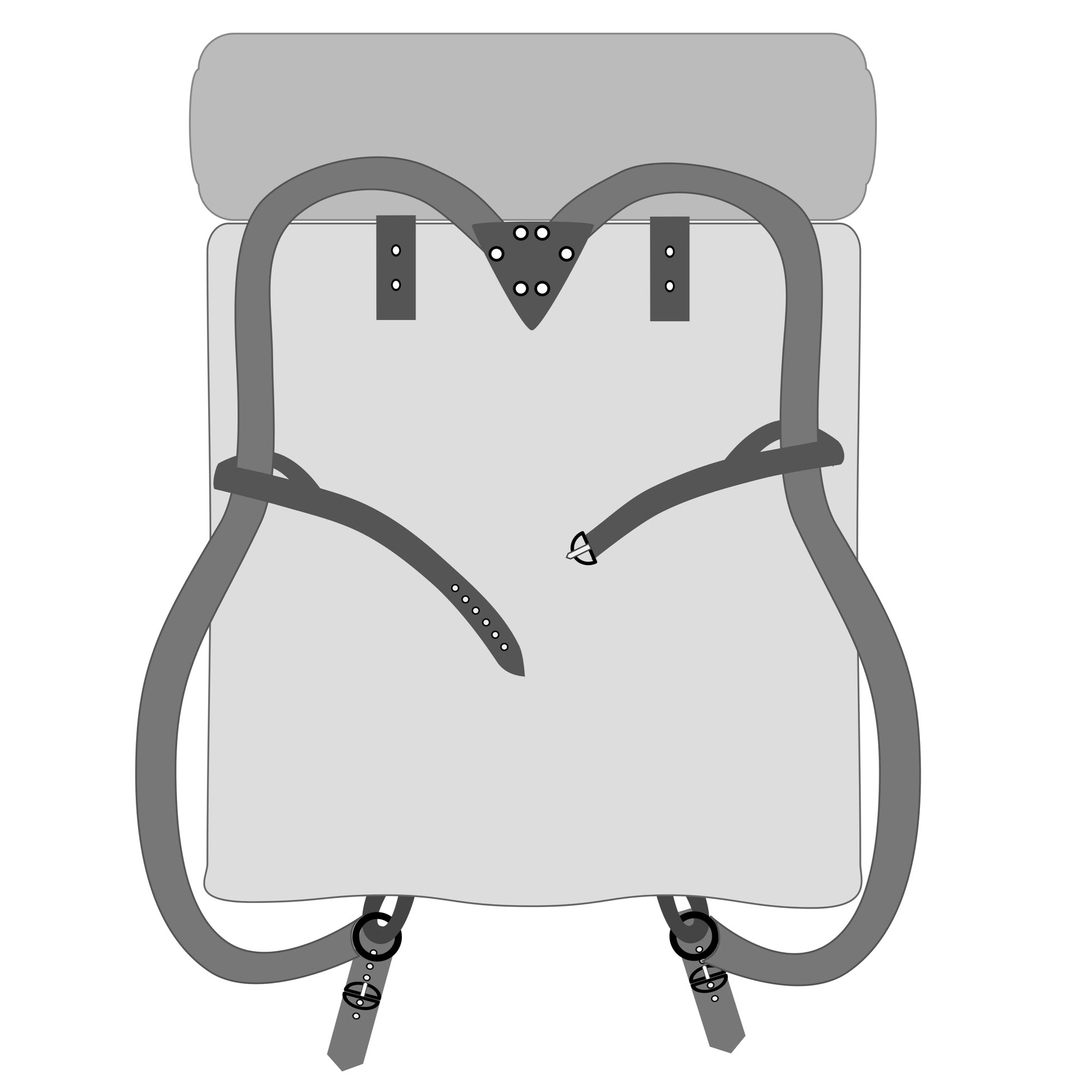

Developed during the earlier War with Mexico, it was widely used before our great civil war by Militias, but save for a scant few exceptions, saw only action among the Confederate ranks, and not with the Union. Nevertheless it was Simple and yet Functional. It was as noted a single bag, with a large painted canvas blanket flap to cover it, this flap having in turn four ties, and was closed by three buttons, and had russet or black straps to go over the shoulders, and had also another strap to connect these shoulder straps across the chest.

First, to load such a pack, the bag is filled with clothing and such personal items as one may have, keeping in mind that one side will lie against the bearer's back, and so all therein must be arranged with due care (a shirt does well here), and then the pack is buttoned to close it. With the flap there is a bit of complexity. This flap covers the outer side of the pack, and is intended to hold a blanket within its grasp, being large, with ribbon ties, so it folds over and around the blanket. However it is quite too small for that use and so it serves a better purpose to secure a waterproof India Rubber or Gum blanket such as one might have, which may be nicely and easily held by these tied ribbons, better than a blanket. This flap then may be folded up against the main body of the pack, whereby one's blanket may then be inserted between the pack and this flap, and so be held tightly once the outer straps are secured.

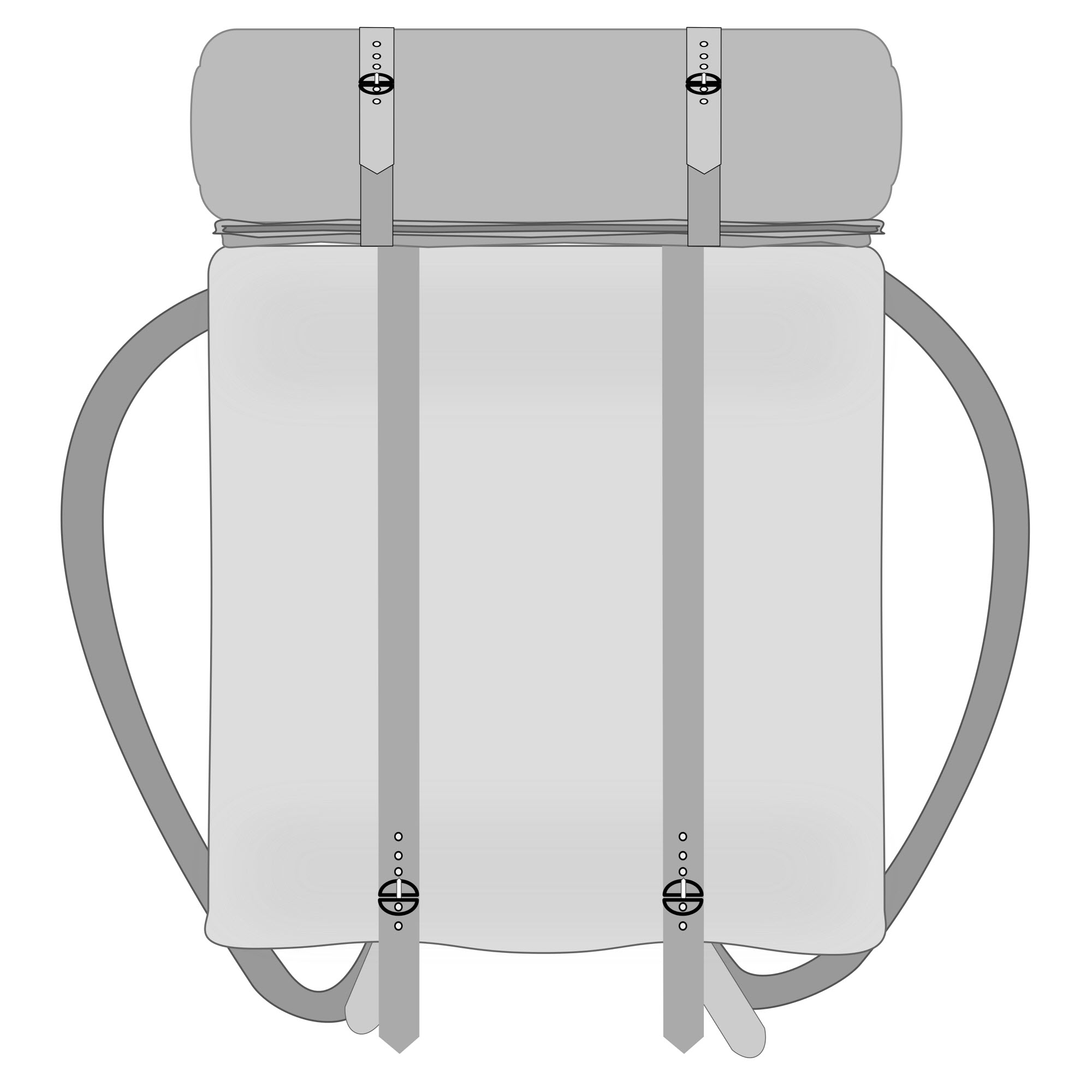

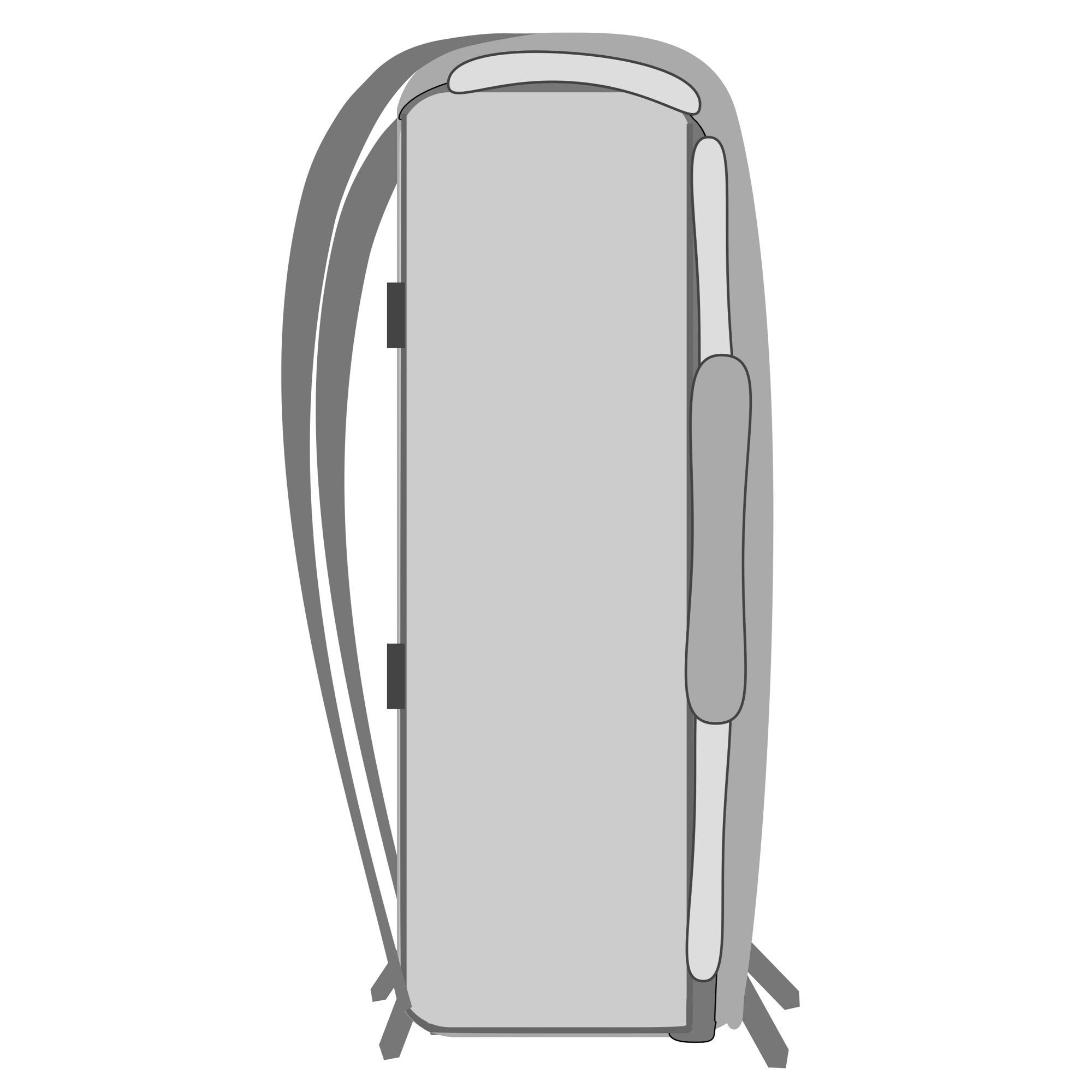

Yet a second style of Knapsack was hard of body, made so by a wooden frame, and this was more common though still rare, having as its frame a wooden box which fitted inside the pack and was either built as part of the knapsack, or sometimes as a removable piece. The typical size of this was 15 by 15 by four inches. Commonly a single large compartment, it was closed by two canvas flaps from its sides, with ties, and had a large canvas cover descending from the top, painted, and having two or three straps to secure it in turn. The frame of this device gave it a convenient and unvarying Box shape, so it was comfortable, and easy to fill, but the frame because of its construction could and did often suffer injury in a fall, or by other means.

Primarily this Knapsack was again in use before the War, among Militias, and was somewhat in its shape like a small valise, though thinner, at only four inches as noted but still held quite a lot. To be filled it would be laid flat with the flaps and cover spread open like wings, and then every corner could be filled with whatever might prove Necessary or Useful, and then the knapsack could be secured by means of the Inner flaps which were tied securely to close this main compartment. Upon this then was placed the gum blanket and tent half, which were in turn held quite safely in place by the outer cover, whose straps performed this function. Atop the pack, behind the head, perched a rolled blanket, again secured by straps, and then at this juncture the loading was complete and the Pack was ready to carry.

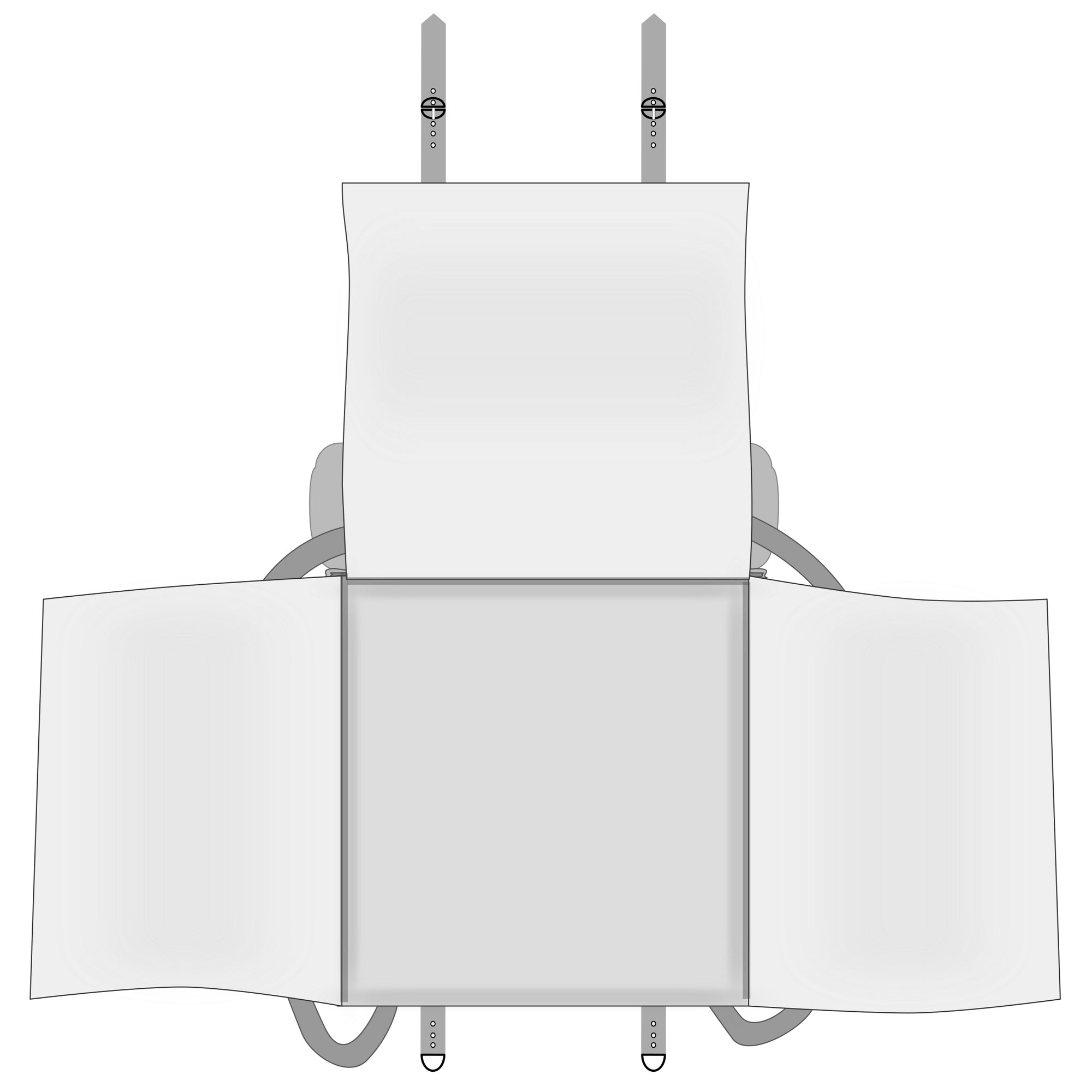

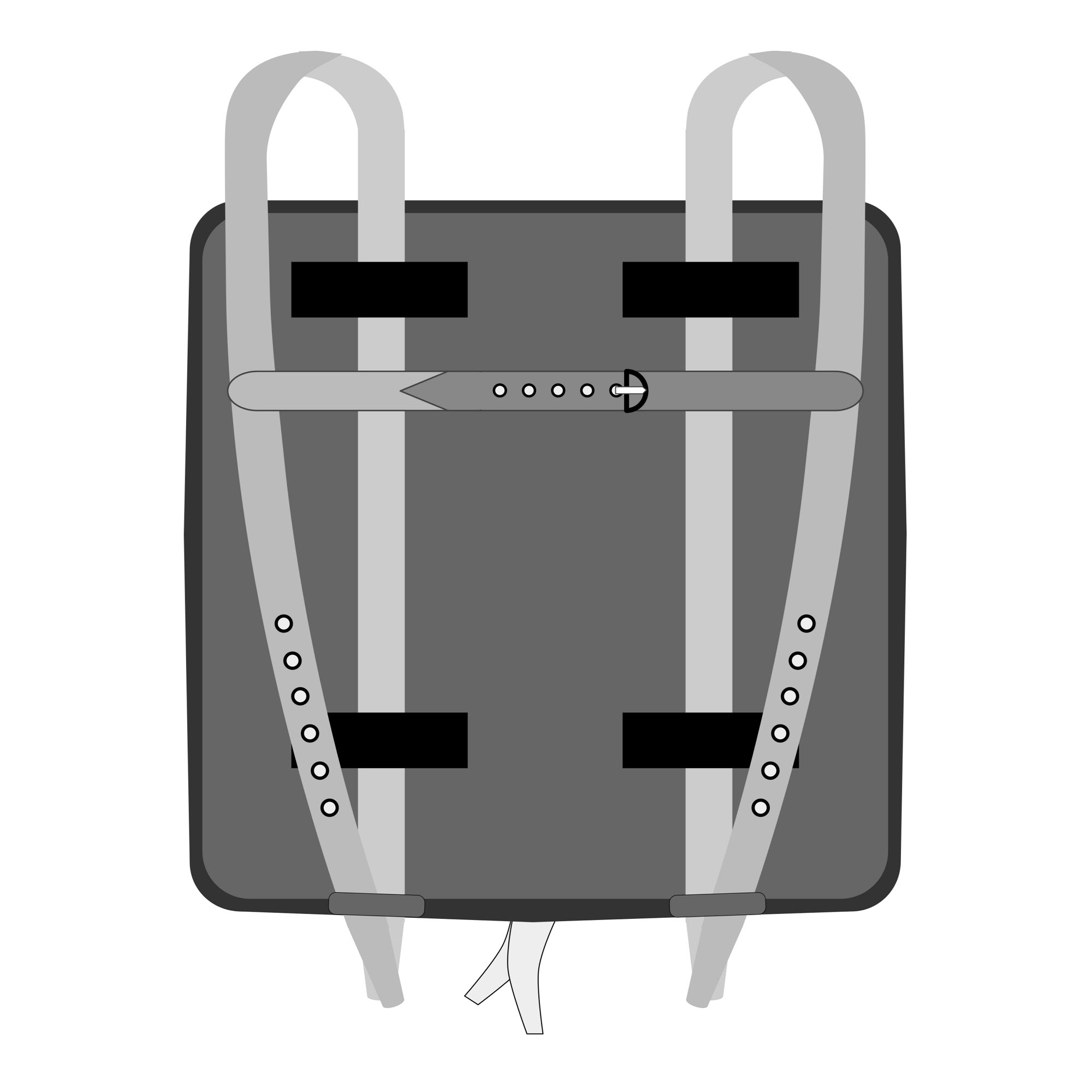

And the third, and latest, and most common pack appeared as the US M1855/1864 Double Bag Knapsack. Its size when fully opened and laid flat was 14 and a half inches in width by 32 and three quarters inches in length, and it had two equal compartments, each being 16 inches long, closed, when the knapsack was folded in half. Although a frame could be fitted to this pack it was in its original form altogether soft and normally remained so. Each of its two compartments accepted a portion of the load, clothing and personal items in one half usually, and shelter-half and blanket in the other, the two halves being held together when folded by the buckling of three straps on the front of the knapsack. The central of these straps served also to hang a boiler or tin cup, and a gum blanket or poncho could be held in between the two halves of the knapsack for easy removal without any need for unfastening.

An extra blanket or greatcoat, if it were carried, found easy stowage outside, upon the knapsack's top, where it was fastened by the usual anchor straps. The pack itself was worn outermost over all accouterments save the canteen, which rode above all for easy access in drinking and refilling, and besides the main over-shoulder carrying straps of the knapsack there were two more, which connected the first two either across the chest, or else partly by crossing the chest, and attaching to the belt with distinctive brass hooks in the shape of the letter J, providing therewith the greatest and most snug Support to the pack.

But there was yet much to be learned through actual experience as even any Knapsack often proved overly clumsy and heavy, and, especially as the war lengthened toward Eternity, this seemed ever more true. The knapsack itself was frequently tossed aside in favor of a plain Bed Roll. The latter had these advantages: First, it was lighter than the pack, and had no digging or chafing straps, and thus afforded greater comfort in most situations. And then its weight could be shifted from shoulder to shoulder as the need arose, and yet in addition it lacked any stiff, gouging corners.

But also there were negatives: The bed roll would not carry as much, though perhaps that was indeed an Advantage in most situations, and it was not as cool in summer. And again, although the bed roll did not prove a material hindrance during walking or even in the midst of certain Strenuous maneuvers, it was not so easily dropped at times of great urgency having rather to be removed over the head than to be simply shrugged from the shoulders as could be done with a knapsack.

General A.P. Hill of the Confederate States was said to have uttered these words: "The road to glory is not encumbered by excess baggage," which sentiment would surely be seconded by all familiar with any conflict, ancient or modern, of any side or faction whatsoever. And if that source might be doubted, then please partake of these words of General William T. Sherman, leader of our own Forces who said, "An army is efficient for action and motion exactly in the inverse ratio of its impedimenta."

With these Ideas firmly implanted in our minds, through use by hard Experience if not by subtle thought, it was a simple matter to learn the correct way of stowing necessaries in a bed roll. It went thus.

Item the first ~ Lay the woollen blanket upon the earth, flat and spread wide, and then fold it once so that its width is diminished by half but its length is preserved.

Item the second ~ Fold what clothes you may have and lay them onto the Blanket, distributed evenly. Perhaps you own a shirt or a spare pair or two of stockings, but whatever you carry, lay all these in. They should be made to lie flat and even, without forming welts, so as to be thin as may be, and arranged in such a way as to present the least amount of bulging as might be possible. Likewise should be added a towel, needle and thread, a candle stub or a bit of paper to write upon, if you carry them, and soap if you have it, all arranged judiciously.

Item the third ~ Now the bed Roll itself must be created through the combined actions of rolling and tying of the blanket. First, having a partner to help is a boon, as this task is much easier for two to accomplish than one, and takes but little time, the benefit being a smooth blanket roll tied well and securely. This result soon establishes its value upon the march. Then when the rolling is done, the finished roll must be twisted and the ends tied shut like those of a sausage.

Item the fourth ~ Now fasten these two ends together one to another, solidly, with a bit of twine or a leathern lace and you are done, and so then slip it on. If hung on the left shoulder the right shoulder will be thus left free for the firing of a weapon. If the blanket roll be hung so, with the tied ends beneath the right elbow, the cartridge box is still accessible upon the left side. These tied ends are best at about the height of the waist belt and the bed roll overall should be fitted to be snug without in the least becoming restrictive of either movement or the flow of air. Then, apply the canteen, last, and hang it so that its straps lie on top of the rolled blanket so as to keep water always easily available and within reach.

Item the fifth ~ The gum blanket, India Rubber blanket or rubber Poncho, should you carry one to defeat rain and dew, may be added, rolled as an outer layer on the outside of the woollen blanket so that it covers the woollen blanket and may protect it against any inclemency of weather, but this may result in greater heating of your body and less comfort on the march. So then as an alternate method the gum blanket may be folded and tied onto the back of the bed roll, and carried behind, or yet again, and perhaps this may be the most agreeable method, it may be rolled separately, and worn as a second roll, lying over the shoulder and alongside the Blanket Roll, and by this means will it allow more nimble access, and also greater Security against loss, though offering somewhat less protection for the woollen blanket during a march in Weather.

But above all, there should be no misunderstanding in these matters, as to whether camping and traveling light has the meaning of doing without Comforts — they do not need to.

There should be a certain degree of pride in so traveling and living in the out-of-doors, and while there may be trifling hardships in so doing, there is always Hardship of sorts everywhere, but less in walking lightly than in transporting great Burdens of useless equipments. Some slight lack of comfort may arise at times, but these will be trifles soon overcome with a bit of Ingenuity and a few days of Experience.

In short, strive to carry as light a load as possible while never attempting to do without that which may preserve Life or Safety, or the essentials of Comfort.

Additionally, I shall pass this along, such as I heard it directly from Patrick Henry Taylor, a sergeant in the 1st Minnesota Regiment of Volunteers:

More fear is felt going into action than after you get in. Infantry are apt to fire high. Cavalry can do nothing with infantry if they stand firm. Infantry seldom cross bayonets — one side or the other will give way in case of a charge before the parties meet. Always have water in your canteen when you go into action. Wounded men must have water. Treat prisoners of war kindly. Pickets should not fire on one another. Always be ready for battle when you are near the enemy. It pays to fix up a comfortable bed. As a general thing, soldiers are very profane.