Stuff It

This end up.

– Let's hear from the terminator. –

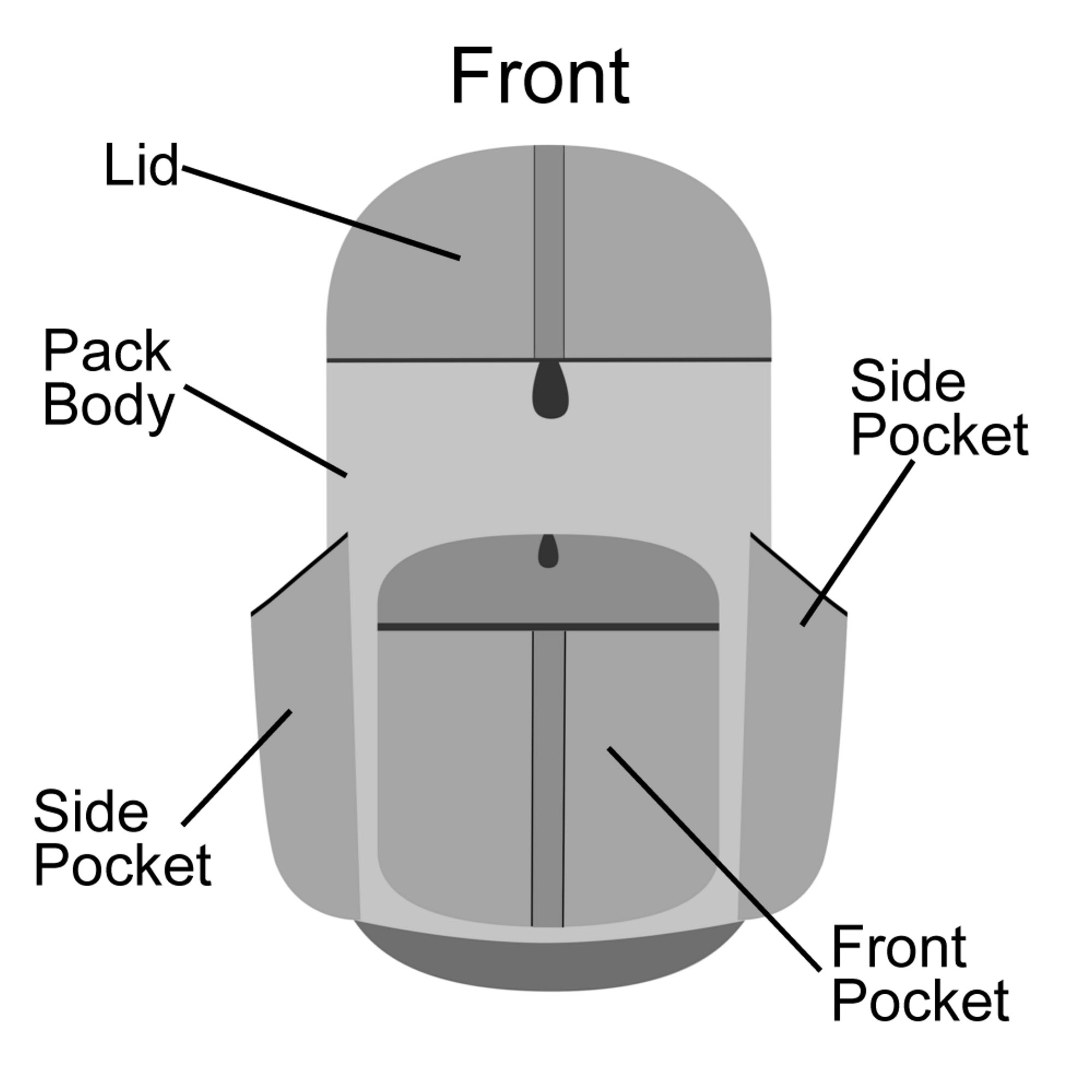

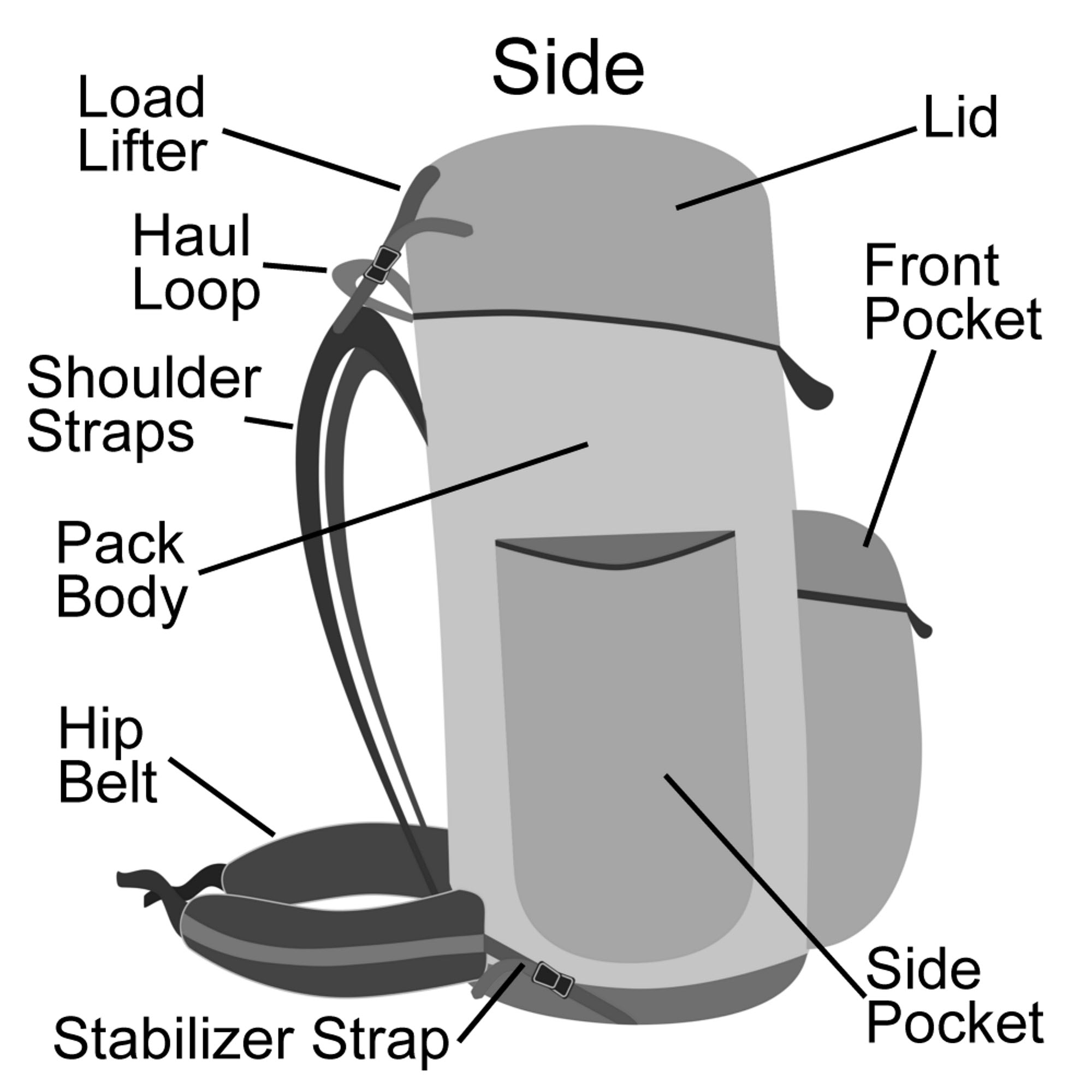

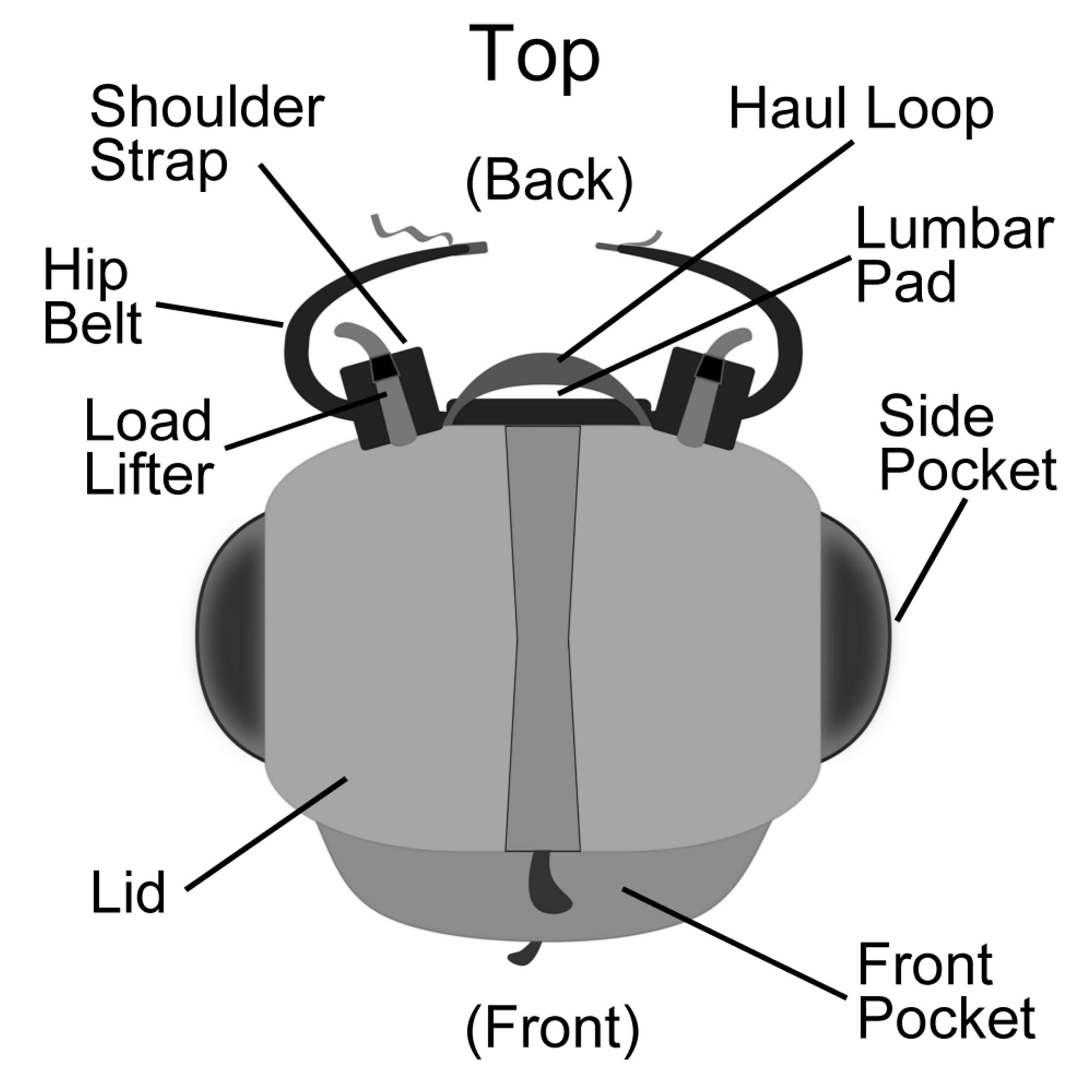

For some terminology.

The back of a pack is the part that goes against your back (your pack likes to go backward). The front of a pack is the part that faces away from you as you walk and toward you as you dig around inside the pack trying to find your lunch. The left and right sides change places depending on whether you look at the pack from the front or the back. (Duh!)

Someone out there somewhere, maybe on a high mountain in still, clear air with the early morning sun gleaming brightly from the dawn horizon has this all figured out, but most of us can't remember if we determine right and left from our point of view or from the pack's point of view, so forget about that. Let's deal with something comprehensible, like the top and bottom. The top of the pack is the part that is up near your shoulders while you hike, and the bottom is the the other end, the part that hits the bear poop first when you set the pack down.

How about that?

So simple once it's explained.

OK then. The possibilities for loading a pack are from the top, the bottom, the front, the back, one or both of the sides, or from many places.

It's getting worse again isn't it? Well hang on a second.

The fun thing is, if you make your own packs, you can do whatever the hell you want, no matter how goofy it might be for someone else. After all, what's wrong with a pack that you can open from both the top and the bottom? Or only the bottom? Nothing at all, if that's the way you like it. No, you won't find one of these hanging from a hook down at Sally-N-Bob's Pack Emporium, or in an L.L. Bean Bean catalog, but who cares? Why should some big company out there in Broken Pavement, N.J. make decisions about what you can have? On the other hand, L.L. Bean did once have some nice bunny-shaped small packs in pink. (They also had bear and raccoon packs, but all of them, each and every single one, were too tiny for adults. Dang. Dang. Oh, dang.)

OK then, let's move on, so very, very sadly.

– Take it from the top. –

Yes, folks, most backpacks load from the same old boring place, the top. You stand the pack up (if you can — unless it's frameless) and shove things into it from the top. You do this either until the pack is full or until you run out of shovable things. If the pack gets full before you're done then you're taking too much or the pack is too small. If you run out of things before the pack is full, then you are trying too hard or the pack is too big. Be more like Buddha or his teacher Goldilocks and find the Middle Way. But without being as annoying as the kid.

The top-loader is the oldest and most basic kind of pack. If you've ever been to to the grocery store and got one of those big old-fashioned paper bags then you know the principle — put stuff in at the top. It's really that simple. So easy. In keeping with this principle, top-loaders are more likely to be one big bag, with no divisions or secret compartments or decoder rings. Most of us can grasp the idea without very much training at all, and then we get on with it pretty well nearly forever.

The beauty of the top-loader is that the last thing you put in is the first thing you get to take out again. When you open that pack what you see is what you still remember having put in there. Maybe your gloves, or your lunch. So nice to see them again, you think. What wonderful times we've had together. Or will have, if what you see on top is your lunch and you want to eat it.

Next you find other things farther down. Things you remember but not so well. Things that bring back memories of sleepy-eyed morning packing, of pleasant overnight dreams, or of yesterday. Ah, yes, bygone times. And continuing to dig you find yet more.

You find odds and ends that you barely recognize, and that you begin to wonder about.

Then perhaps near the bottom of the pack you finally excavate objects strange and arcane, maybe from another world, or from an extinct ancient civilization that got its thrills lurking in alternate dimensions and leaving behind inscrutable and disorienting doodads for you to find at odd times. You are baffled by artifacts whose uses you can only guess at. Widgets that may in fact even be frightening, or which appear vaguely evil, that have strange dials and gauges on them, or which vibrate and buzz faintly when handled, and grow disconcertingly warm or cold in the hand, or are simply soft, damp, and fuzzy with mold. And you have no idea what they are or where they came from. Especially the moldy ones.

But not to fear. They are all yours. You just forgot about them for a while. Because unloading a top-loading backpack is like an archeological dig. It's layer after layer of discovery, right down to the bottom. It can be fun to do, unless your rain jacket is down there in that dark hole and the sky is falling all around you in golf-ball-sized gobs that splat loudly and bounce off the ground, and everything you brought is spread out around you, in the mud, and you are swearing a lot, which is pretty common in these circumstances.

At times like these you wonder why you didn't buy a panel-loader.

– Roll down that wall, babe. –

The idea of a panel-loader is the same as the union suit.

Example one: Think of a shoe box standing up on one of its small ends. Kind of that shape. Now make it as big as a backpack. Then rotate it in your mind so that the side that is normally the top (where the lid goes) is facing you. Now imagine a big zipper going up the left side of that, across the top, and down the right side, like the zipper on a suitcase. The flap that falls down when you undo the zipper is the panel.

Example two: The union suit (or Idaho Space Suit) is that one-piece long underwear thing with the flap in the back. The flap is called the access hatch, drop seat, or fireman's flap, depending on where you're from and what you like to think about. All three names describe the same great idea though.

Apparently the union suit started out as a revolutionary type of women's underwear known as the Liberty Suit (at least among Louisa May Alcott's friends). It was an alternative to nasty tight bony things with hooks and laces and hinges and so on that left marks on the skin and scars on the soul. Manly men never wore corsets much in polite society, or seldom admitted to it, but eventually they were overcome by the fascinating kinky possibilities of the union suit and officially declared it to be Tough Guy Wear™ and OK for all-terrain use.1

Anyhow, by then women had lost interest in the union suit and had moved on to thongs, sports bras, and sweat pants, and had left the scratchy gray misshapen thing to men, who still treasure it dearly. And, perhaps due to an innate, possibly pathological fascination some have for secret access hatches, we later gained the panel-loading pack.

OK there.

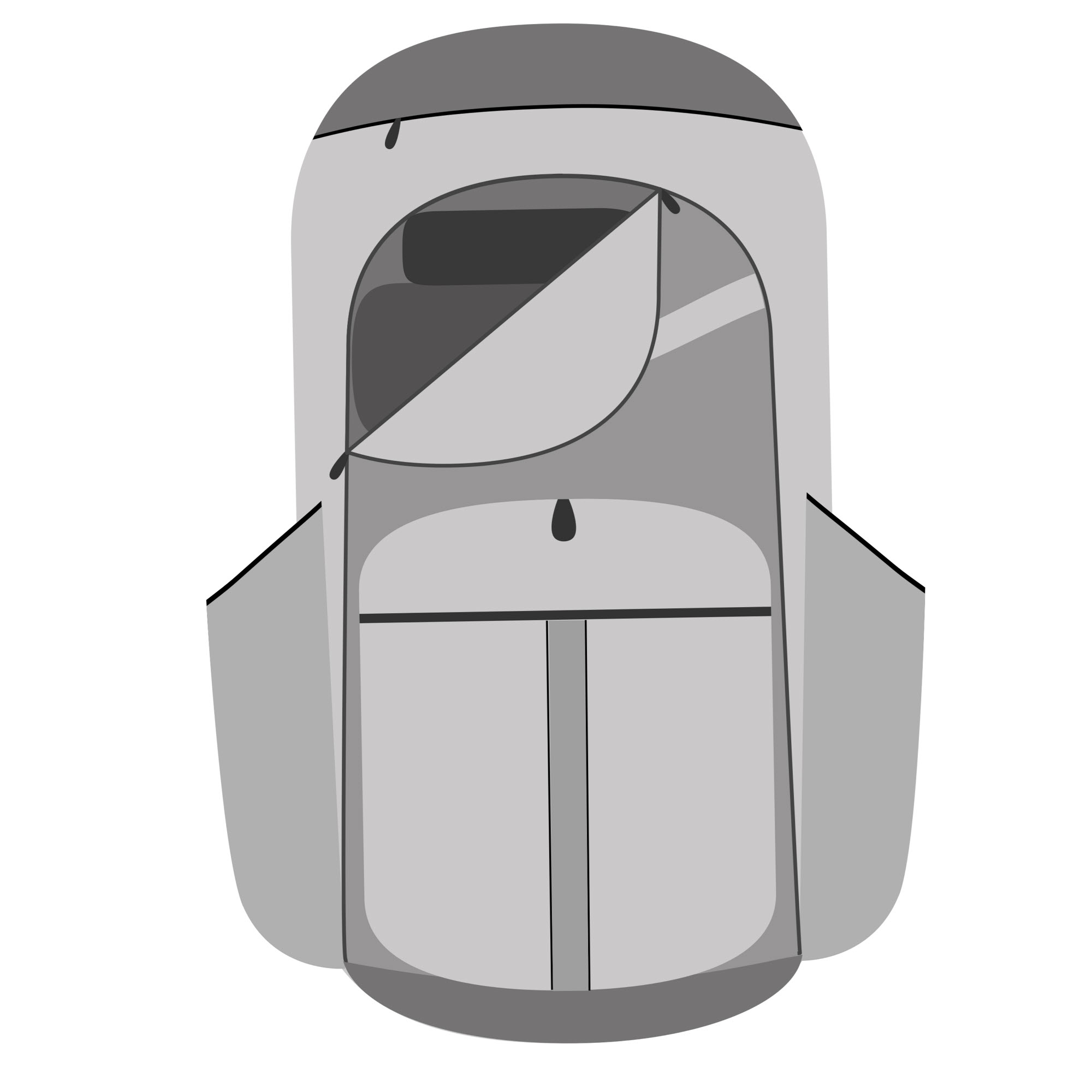

Generally panel-loaders have one big compartment inside, and they are front-loaders, which means that they load from the side away from your back. (Remember?) While the top-loader stands upright with its maw open like a young bird in a nest at feeding time, a panel-loader is usually going to be lying on its back and yawning. (Panel-loaders are much more laid back, in case you haven't guessed yet.)

To fill a panel-loader, first you talk to it gently (to get it into a relaxed mood), then you rub its belly in a slow and non-threatening sort of way (to relax it even more). Then when you're sure it's safe and the pack is fully ready for your next move, you slowly begin the unzipping part and lay open the flap. If you move too fast, or accidentally get tickly, the pack may scratch you or bite, so be careful, especially with a new pack that is not used to being handled.

Slow and steady now...

Lay in your goods and arrange them carefully in layers, the softest stuff first, in where it will be near your back, being sure to fill all the corners, getting things nice and cozy and tight toward the bottom of the pack. Finally, when you are done, simply zip the sucker back up and head for the hills. Don't pay any attention to the mud, dust, dead leaves, and bugs all over the shoulder straps and the back of the pack. That's supposed to be there, and you won't see it anyway, while you hike — all that stuff got there when you laid the pack down to begin loading it. Too bad.

So then, at the end of the day you can stop a bit early and clean up. It isn't a big deal. Mud comes off, especially after drying all day. What might be a big deal is finding that sometime during the last eight hours of hiking, your big long zipper broke and some mighty interesting and useful things fell out of the pack through the open panel. Of course you didn't see any of this because it happened way out back in your giant blind spot, but you'll probably live through the experience. If you are lucky.

Unless one of the things you lost was your mouse repellent and a ravenous horde of them swarms you at midnight, when your little eyes are closed in sleep and you are wrapped up nice and tight in that slim sleek mummy bag and can't even wave your arms around in futile gestures of mock threat. Yeah, well.

– Peek-a-boo loaders. –

Let's invent this as our secret term for packs that have several access hatches. Some packs are like that.

Normally these are called compartmented packs, and they usually have an upper level and a lower level, both accessed through the front, or from the top for the upper part, and through a front panel for the lower compartment. Other than that they are like other panel-loaders.

The bottom compartment is advertised as the place to put your sleeping bag and the upper one is for the rest of your things. Of course these packs have frames, and the frame makes this sort of pack workable by keeping it upright and taut. When your pack has a frame it's easier to arrange your goods in a definite sort of way, keeping the lighter and bulkier things down low, and perching the weightier things up high, near your shoulders, where it's easier to keep them balanced over your hips. Especially if you don't have quite enough to fill the pack to the brim.

A lot of compartmented packs have two or more zippers so you get multiple chances at experiencing zipper failure, but pack makers are not dummies. They add extra straps, which can fill in for exploded zippers. Kinda. So you get more weight and more complexity absolutely free with each pack.

– Side show freaks. –

Then there are the other options.

You won't see a back-loading pack, at least not without hallucinating. On commercial (heavy) packs from major manufacturers, the back is where all the padding goes, and some of the levers, dials, thumb screws, and pressure release valves. And maybe the fuse box. There's no room for anything else there, and it all would get pretty lumpy against your back anyway, so forget about that option.

But there are a couple of serviceable oddballs.

One the author (Yay, me!) worked on for his own use is what you might call a slit-loader — like a panel-loader without a panel. The pack has a top and bottom, a back, and two sides, but no real front. It just has two pieces of fabric there, and they come at each other from the left and right sides like a theater curtain, but they also overlap a little.

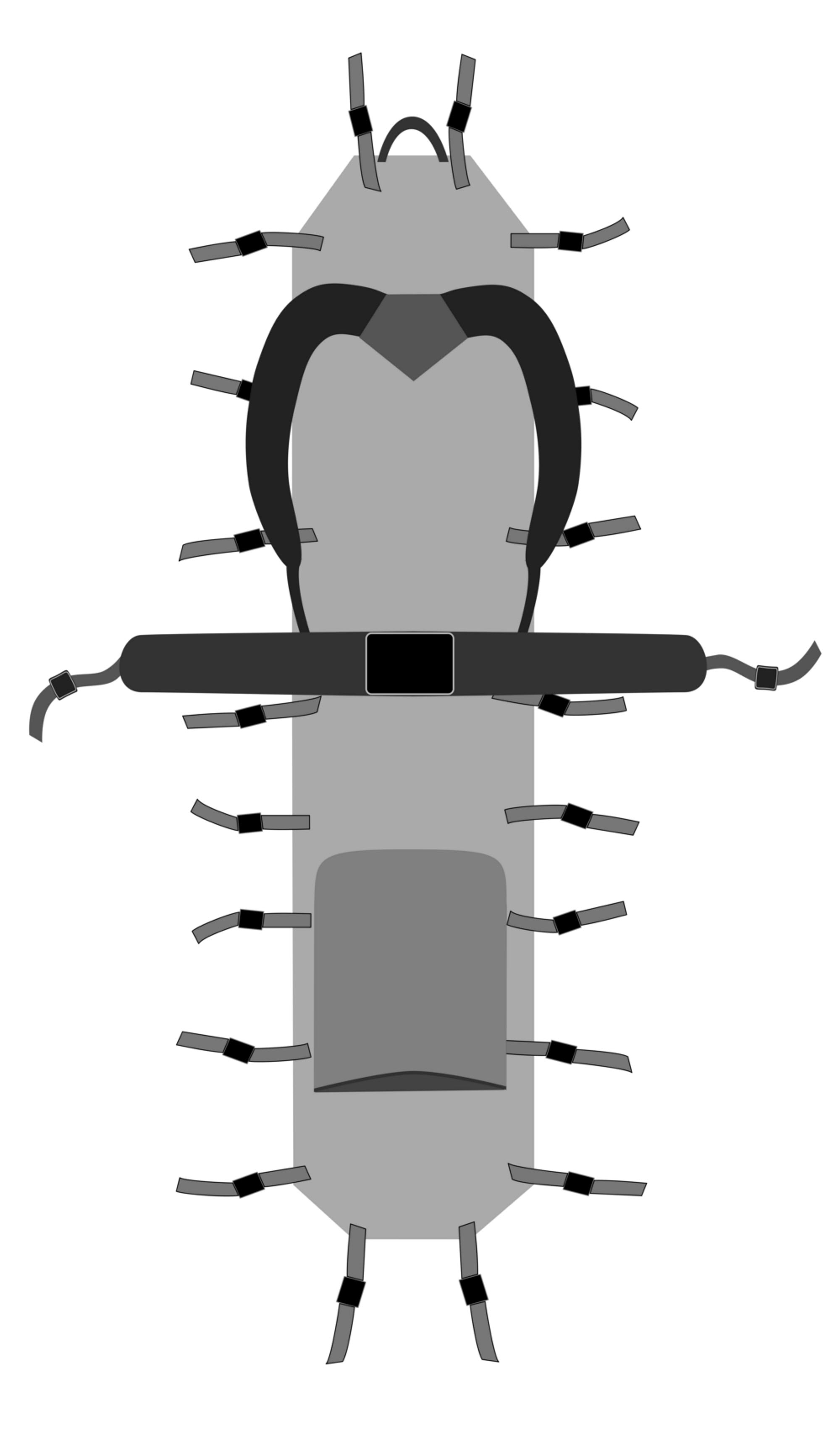

The pack works by compression. You load it by stuffing your gear in through the slit, which is like the fly on your tighty-whities, except that it allows free access all the way up and down the pack's front. After loading the pack, you cinch it tight with compression straps.

When cinched down hard by five or six horizontal straps, the fabric flaps on the front side overlap even more, as they are pulled together, close up completely, and stay closed. The pack becomes rigid as a stump, and your things stay inside, locked solidly in place, and the whole pack becomes a giant, firm, frameless but well-shaped bundle with shoulder straps. One that doesn't wobble or flop, and which stays pleasantly stiff while remaining comfortable.

A compression mechanism like this works for ultralight packs when the hiker has nothing as rigid as even a foam sleeping pad to stand in as a frame. If instead of camping on the ground with a tent or tarp while using a normal sleeping pad, you sleep in a hammock which has only a soft, floppy under-quilt, then you carry nothing at all rigid enough to fake it as a frame, but compression can do the job instead.

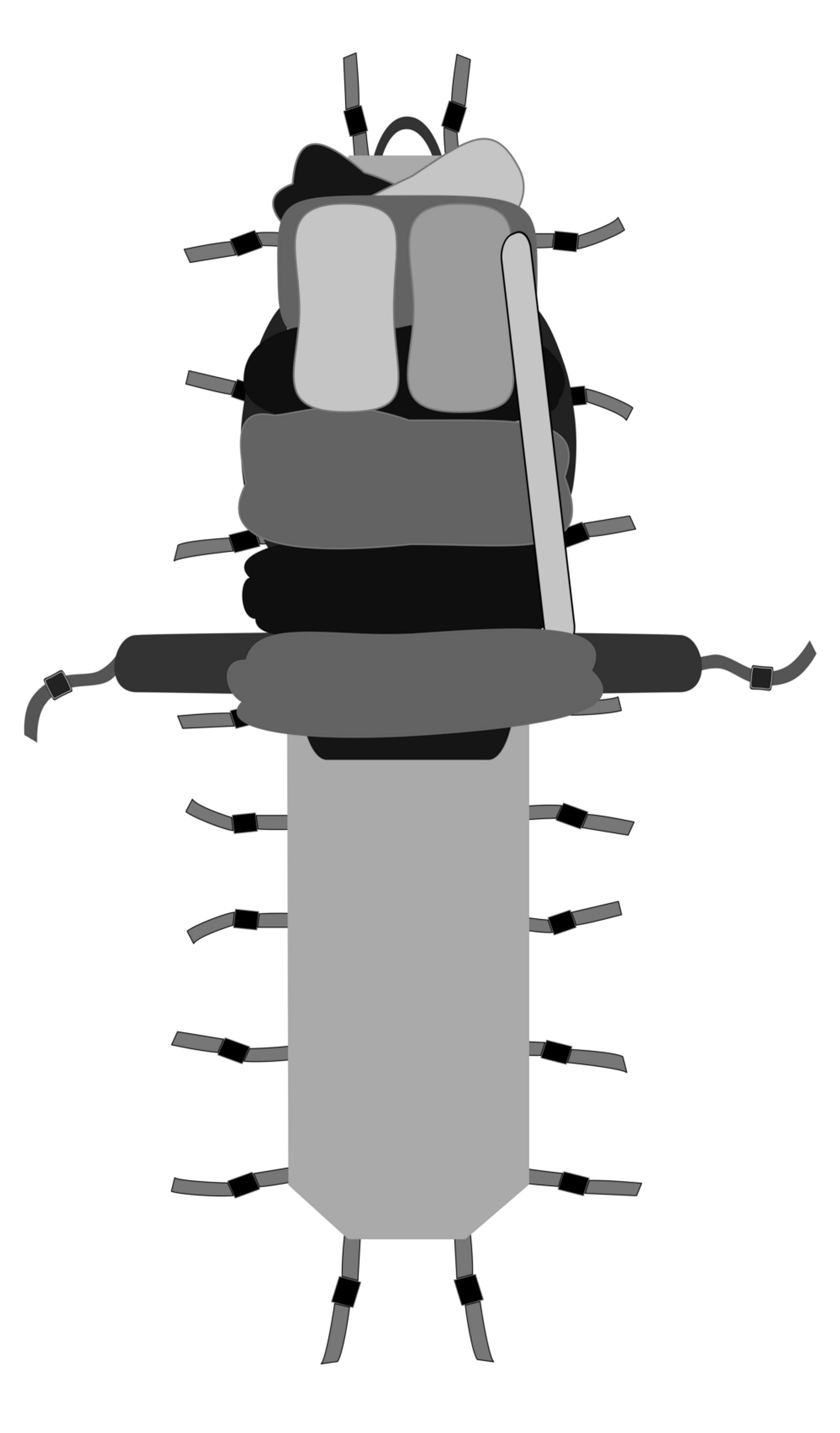

The other type of oddball pack we can call a hugger. This is similar to a slit-loader with two slits, but is actually made commercially by a small company, Moonbow Gear. The pack is the Gearskin. You can call this a side-loader or a panel-loader or a top-loader. It is all of these. The pack is only one continuous long and narrow sheet of fabric, with shoulder straps and a hip belt attached to one half of one side of the fabric sheet. There are compression straps along the edges.

(Some equipment bulges out around the edges.)

(Some equipment bulges out around the edges.)

To load it, lay the pack (i.e., the sheet of fabric) flat with the shoulder straps and hip belt underneath, on the ground, pile your gear on the half-side opposite to the shoulder straps, and when done fold the other half of the fabric up and over everything to end up with something like a stuffed taco shell.

Then fasten and tighten the compression straps which run along the edges. These straps pull the pack's front and back sides together and make it all tight. The pack compresses into a flat, wide wad that lies tight against your back. Its empty weight is one to one and a half pounds (450 to 680 g) more or less, depending on the size you get and the type of fabric used to make it, and its volume is variable.

Either of these last two designs is like the panel-loader in wanting to wallow on the ground during loading. Since the Gearskin is a flat piece of fabric it is especially maddening to load on a slope (where you can sleep if hammock camping), when you put some things in (actually on) the open pack, and then they slide off and roll away downhill as soon as you reach for the next thing, but the pack is simple in design, and is a terrific choice if you have at least three arms to work with.

The slit-loader (or Squeezo Pack as I call mine) keeps its bag identity even when lying flat, since it doesn't open all the way, and is easier to load on odd terrain, but doesn't have the Gearskin's advertised volume flexibility of 2500 to 6500 cubic inches (41 to 107 L). My pack design runs from about 2500 up to 3000 cubic inches (41 to 49 L), and is trending a bit smaller, though it makes up for lack of internal volume with huge (and extremely convenient) side pockets. Loading the Squeezo is something more like blowing up a balloon than loading any ordinary pack — fussy in its own way too, and definitely not for everyone.

– Getting back to normal. –

What kind of loading option you choose is up to you. There is no accounting for taste. You can be like the woman from Normal, Illinois who said "Yes!" to a man from Oblong, Illinois despite the inevitable headline — Oblong Man Marries Normal Woman.

You and your pack may be like that, or vice versa, and no one else should think it's any of their business. They will, but you can always poke at them with your trekking poles, or tease them until they start hissing and hyperventilating, or whatever you want. The real point is knowing the options, which are basically to shove stuff into your pack from the top or from the front. Or from some other angle if you like to hang out on the lunatic fringe. If so, then every widely-accepted, uncritically-held idea (Because we've always done it that way — just because!) is only another chance for you to prove that you are smarter than you look, or at least stranger than anyone had suspected.

Dig it. It's your field to play in.

– Wait! Let's hallucinate first. –

Remember that no no back-loader statement from a few paragraphs back? Well, it ain't completely true, and no hallucinating is needed either, unless it pleases you.

There is one pack that loads from the back (the side next to your own back). The Jensen.

If it was ever valid to say more unique, that phrase would stick to the Jensen Pack the way a hungry octopus sticks to a crab. The Jensen is more superlatively uniquer than anything else.

The Jensen is a soft pack design that preceded soft packs, and a frameless design that preceded frameless packs. It was clever and light and supple in an era before anyone thought that packs could be that way, or thought they wanted one like that. If you have a really good memory, recall that the Jensen got mentioned back in the history section. It's made by Rivendell Mountain Works.

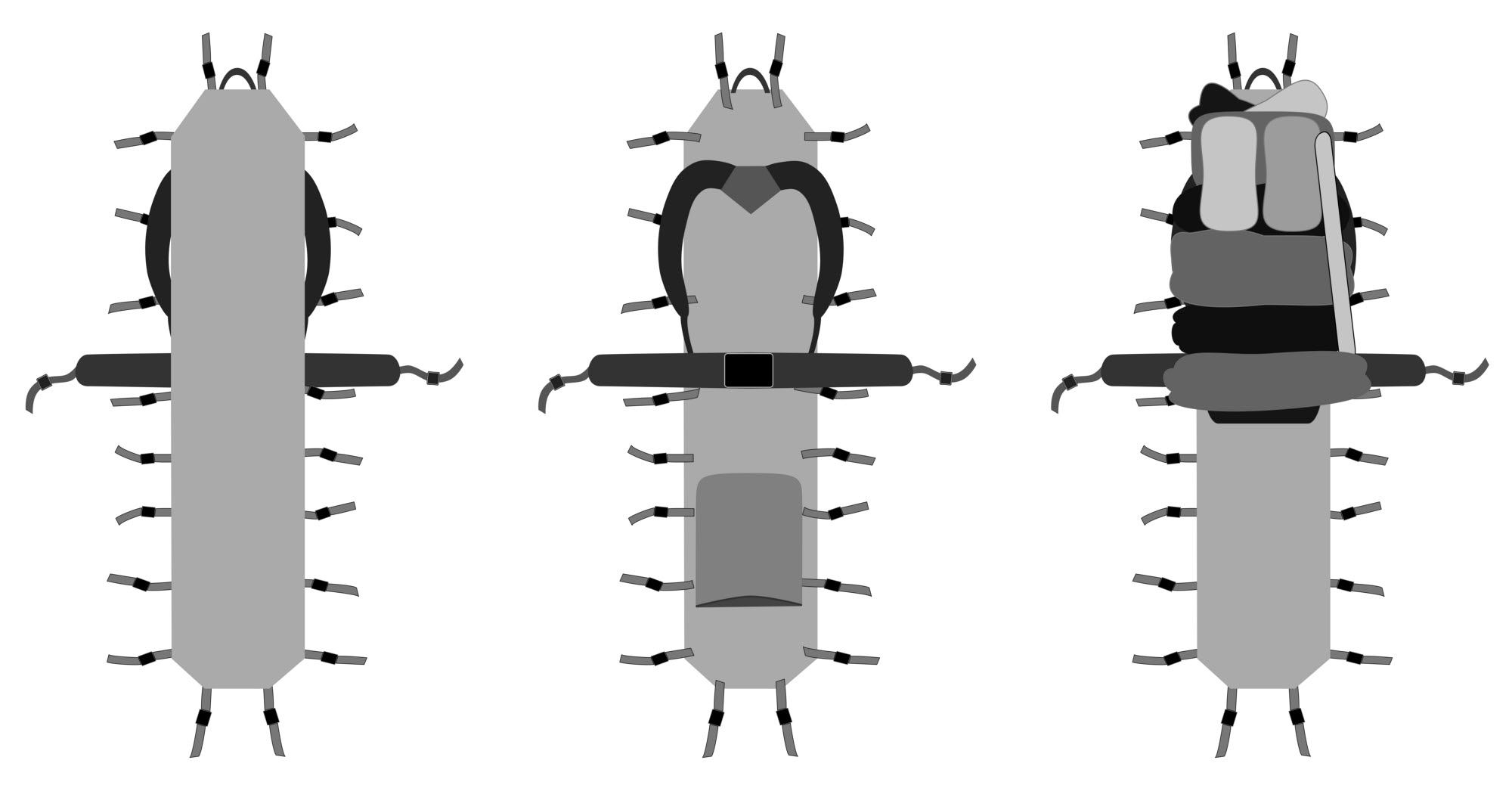

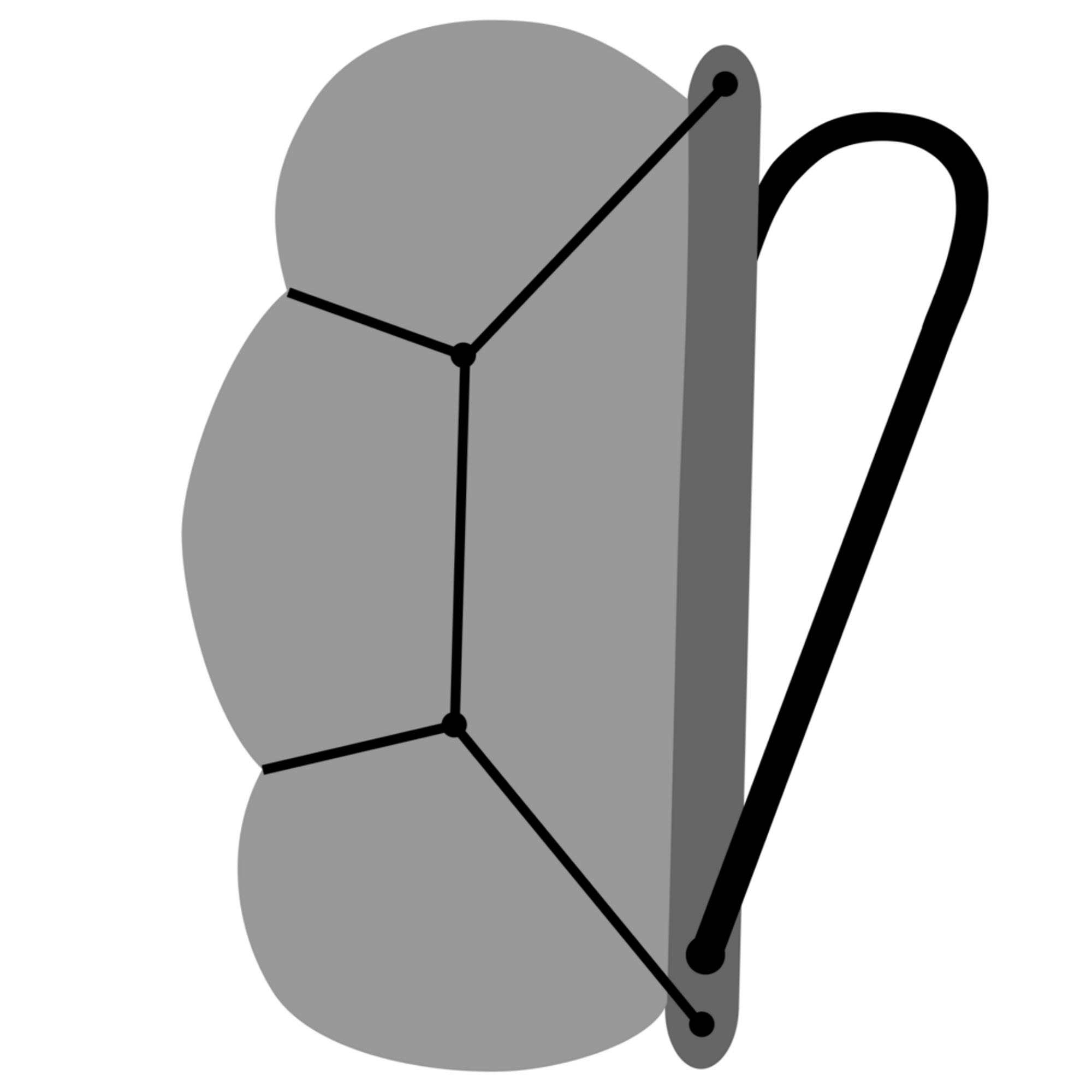

The Jensen has two compartments. The bottom one is like a fanny pack that wraps around the hips and sits on top of them like a hip belt. Carry a small load and you can get it all in there.

The upper compartment has a zipper closure on the back side, and has a sewn-in vertical divider. This divider creates what amounts to two parallel vertical tubes comprising the pack's upper compartment. Stuffing these tubes carefully, and hard, produces a rigid pack whose upper compartment stiffens itself and is supported from below by resting on the bottom compartment that hugs the top of the hiker's pelvis.

Got it?

All this has the effect of putting the pack's weight on the wearer's hips, naturally, while providing rigidity in a complementarily natural way.

First the lower compartment gets stuffed to the limit, with a sleeping bag and whatever else can be poked into it, and then the two vertical tubes in the pack's upper compartment get loaded. These tubes end (on the inside, of course) just short of the pack's top, so there is some expansion space there where more big fluffy and lightweight things can go. This top area gets pulled up and forward by the shoulder straps when the pack is donned, which helps to keep the load balanced front-to-back.

To load those two upper tube-compartments you lay the pack down on its front (the part that goes away from your body). So if the ground is muddy or dusty, you never get that mud or dust on the back of your shirt because it never gets close to you. Then you zip the back open, and as you fill this upper part of the pack, you slowly work the beefy zippers shut again, compressing the load. When you are done the pack maintains its shape by means of this compression.

No, I've never seen one either, but the name is so cool. Rivendell Mountain Works. Mmmm.

– Footsie Notes –

1: Union suit: http://bit.ly/1zL4dYI and http://bit.ly/1yx7qhf