History Packery

What you didn't know but soon will

– Dumbing down deep. –

You've read dumb articles in the past. A hack writer introduces a subject and feels that it needs some depth, so there's a brief nod to history, which the writer invents. Something about the knuckle dragging cavemen, and then maybe something about knights of the round table, followed by scenes from the wild west, the roaring 20s, then finally the author starts on the real subject.

This kind of fluff usually covers half a paragraph unless the writer is totally clueless and trying like crazy to fill space. Then it can take up to half the article.

Which is the point. Turn the crank. Make up something. Blow smoke. Fill space. Give the readers something to keep them busy. They're dumb anyway, right? They won't catch on, so fake them out. This is standard hack writer procedure.

So let's start with some history then, cave man era.

It's easy to say that people way back when made bags to carry things in because they did. People still do. But the really old stuff was made of all organic, all natural materials without price tags. And what were those all natural materials? Things like hides and branches, a few strips of leather, and sinew.

And that was all they really needed. It's easy to say that these people had a few odds and ends to drop into their packs because they did. Perhaps a stray elk liver, or a couple of rocks. They didn't have much because shopping malls were too far away to drive to, and anyway no one had a car that would go several thousand years into the future and come back again, unlike now.

And there was no shopping. Or money. And what transportation existed was unreliable in the extreme. And might try to eat you.

These people were stuck with only odds and ends then. Stuck.

With odds.

Odds like lumps of dried meat (an elk liver only if you were very wealthy), and ends like tubers, tanned hides, some semi-pretty shells, or clods of dirt. And at this point we simply wave our hands and say that after history's wheel turned a few turns we got the modern backpack, cleverly skipping all the messy details like how to get an elk liver into your handbag.

It got even easier to say this when Frozen Fritz showed up on a glacier near the border separating Austria and Italy in 1991.

Strictly speaking, Fritz was only partly on a glacier. The rest of him was partly in it. He's more often referred to as Ötzi the Iceman, and he's been dead roughly five thousand three hundred years.

Earlier news reports said things like "He wore a wooden-framed backpack on his back and carried a bow which he had not yet finished making. He had a quiver full of half finished arrows with bone and stone arrowheads which had not yet been attached. He wore a small pack with his fire-making kit around his waist. And hanging on the strap of his pack was a stone knife in a woven grass sheath. He also carried a copper-bladed ax." 1

And in case that wasn't enough, they brought in experts to pontificate: "The picture that emerges from my analysis of Ötzi's possessions is of a mature, highly skilled hunter. His kit provided, with minimal weight, all the necessary tools for hunting, butchering and bringing back meat, skins, antlers or horn on his lightweight pack frame." 2

Damn handy for the quickie historian to find this stuff in print, already typed up, although later on people began rethinking the evidence. Like maybe what the experts first took for a pack frame was really part of Fritz's snowshoes. Whoa, babe. Too bad for us lazy authors. This book is about packs, and it would be so easy to drop in a few paragraphs of canned history.

Dang. More typing must be done the hard way, I guess. By me.

But there was a Fritz, and he was frozen, and it is clear that he had some pretty tricky gear, and knew how to use it.

Snowshoes, for instance. You didn't get them off the rack 5300 years ago. There were no racks, except the kind that might come after you on the top side of a moose.

So in other words he (Fritz) and his people (the ancient Fritzians) could get by.

They were bright and capable, and we know they had to carry things, that's pretty obvious, so they probably had packs. External frame packs are such a blindingly obvious idea that they were even reinvented in the 20th century. Therefore Fritz's folks likely had them too, illustrating the eternal cutting edge of European culture which we have gradually come to know and love.

Note also that mention of Fritz's fire-making kit. He definitely did have a small bag or pack with him.

Fritz's external frame backpack is not confirmed, but he did have a day pack, as we would call it. He also had a half-finished bow and a bunch of half-finished arrows, so we can also say that he was a lazy bastard. Someone a guy could trust, maybe hoist a few brewskis with on a Neolithic Saturday night when it could feel really good to sit around the fire and gnaw on something.

Maybe Fritz was the kind of sloppy, easy-going sort of guy whose shoelaces come undone a lot, the kind of person who has a bunch of stories to share.

Maybe that's why they shot him and left him stuck in a glacier. No one has ever liked a smartass.

– Please to ignore gap. –

Of several thousand years.

(Please.)

Next we skip a few thousand irrelevant years and hop up almost to the present day. We can do that because we're not historians or anthropologists, and because none of us is deeply interested in this. You have no unhealthy fascination with history, either. Maybe a little interest, around the edges, and that's OK, but not more than a little interest. That is OK too.

You're OK, I'm OK. Are we OK with that? OK.

Besides, since you're reading, and this is all in your head, it's pretty easy to hop around. If you're anywhere near normal then you have lots of room in there, which makes hopping easier. (Have you noticed?)

So then. The 20th century arrives, but just barely.

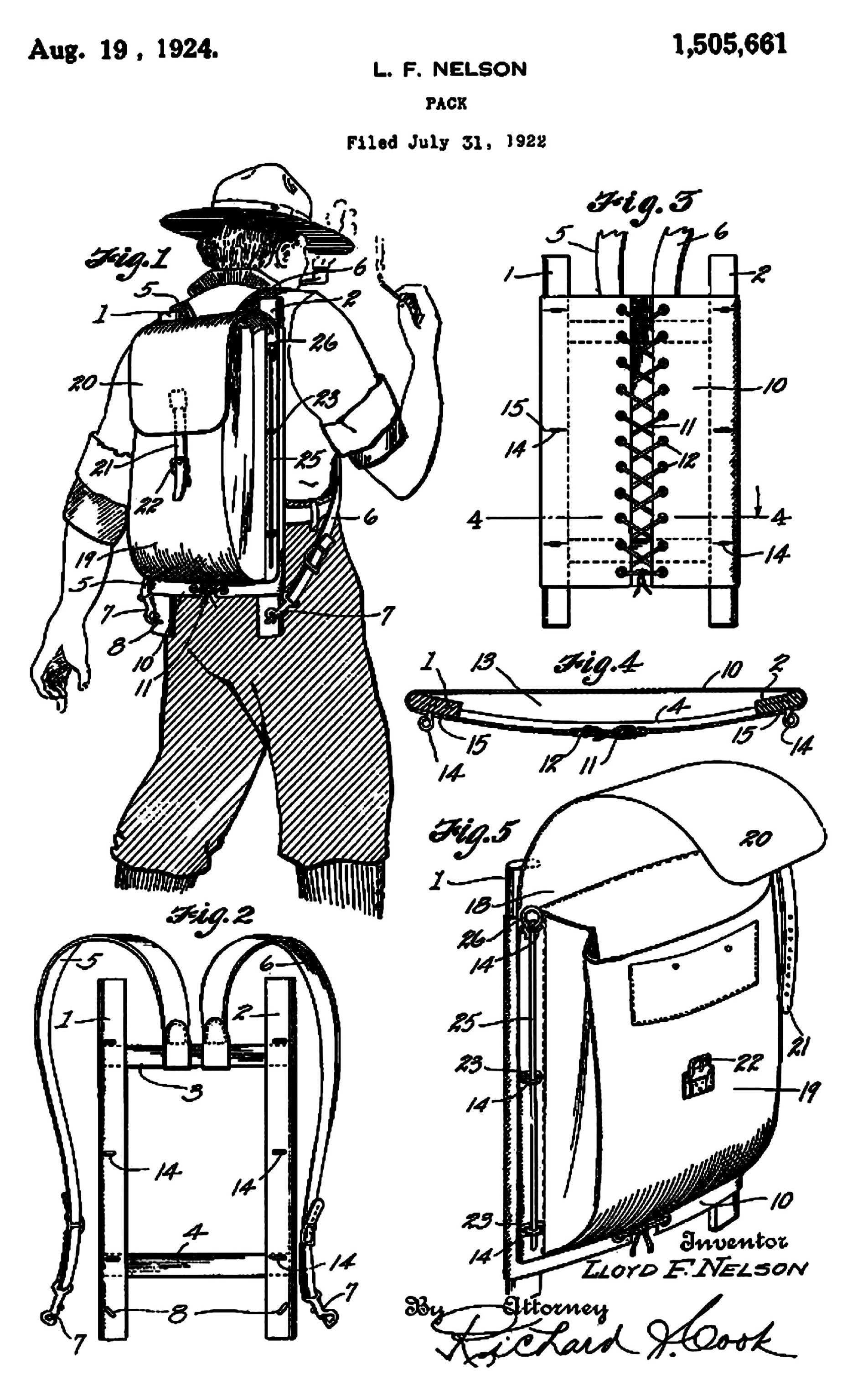

There is this guy named Lloyd F. Nelson. For some reason they always spell Lloyd with two ells, and Lloyd F. Nelson was one of them. Damn straight. A government employee, working for the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, WA very early in the 20th century.

One day his job took Lloyd F. to Alaska where he faithfully performed his duties. He was a guy you could count on, this Lloyd of the redundant ells. He performed duties faithfully no matter where he was and no doubt would have used his spare ell with barely a moment's notice if he had ever needed to. But with Lloyd F., that probably was not necessary.

So he went to Alaska on assignment and did something, whatever it was.

But after he was done with whatever it was, Lloyd had a few days off and borrowed a "crude Indian pack board made of sealskins stretched over willow sticks, a style used by generations." Maybe it was crude and beat up, or maybe he didn't at first recognize its hand-crafted authenticity, but the pack did give him an idea.

What Nelson used was probably two or three sticks lashed together, forming either an A shape or a triangular shape (depending on how many sticks were used, how they were tied, and whether the maker had learned his letters).

The sticks were the frame, and the frame had a bag tied in the middle somewhere, with a couple of shoulder straps thrown in for fun. This was 1920, so calm down. In 1920 this was really something. This was the same kind of technology that Frozen Fritz had used five millennia before, but reinvented by some other clever northern American Indian types, after which it hit this regular Lloyd between the ells with its brilliance.

Us pasty white people catch on eventually. "Brilliant", he said, did Lloyd F. say to himself one day.

The story, as it is told, is that after his epiphany Nelson lay awake nights and fretted over whether he could come up with something better. As in better than three sticks and some hide.

Being a slow and methodical genius, Nelson continued this process for nine years. (Nine.)

During this time Nelson designed many packs, learned to sew, had wooden parts made to his specifications, and tested his packs by actually using them, throwing in canned goods and rocks to make things completely authentic in an early 20th century way. He worked and worked and worked, and when he finally had it right he worked and worked and worked some more, and then he went out and tried to sell his new pack.

Nope.

Didn't sell.

No one was interested. Only a few packs eventually sold in a desultory and sporadic way, which means hardly at all.

Finally, something happened.

But not to Lloyd F.

The packs did not sell, or attract any attention, let alone purchasers. At all.

So, groping toward the advertising world as a last resort, a tactic many other geniuses have resorted to, Nelson decided to name his product. He named it Trapper Nelson's Indian Pack Board, and then later decided to ignore the paid advice, live dangerously, and shorten the name to Trapper Nelson. Not Trapper Lloyd F. Nelson with two ells but just Trapper Nelson, as in the Trapper Nelson pack. Which is now famous.

But it wasn't then, you see.

Because it continued not to sell. Or if you are fussy about cause and effect, it was not-famous because it did not sell. Either way works. The pack was in full-on failure mode.

In fact, this lack of sales was positively furious. It furiously did not sell at all.

Then Nelson patented his invention, which made a huge change because the pack did not sell even more than it did not sell before. And then Nelson tried everything else he could think of.

People continued to stare at the pack board and grunt to themselves while scratching their behinds. The very people who most needed Nelson's invention simply could not comprehend this technological leap.

Going from a dumpy canvas bag with shoulder straps to a dumpy canvas bag hung on a wooden frame to which the shoulder straps were in turn anchored was too big a leap. Simply too big a leap. Too much for them to imagine. They only grunted quietly over and over again, while staring, and not in a reflective or sophisticated sort of way either.

Grunt. (Time passes.) Stare.

Grunt. (More time passes.) More staring.

Silence.

Grunt.

Maybe it was the canvas panel across the back, designed to prevent the frame from digging into the hiker's spine. Perhaps it was the concept of hanging the bag on the frame to keep it away from the hiker's body, and then hanging that frame thing on the hiker's body, with the aforementioned canvas panel providing ventilation and holding the whole arrangement away from the hiker's back. Or it could be that the idea of the wooden frame was the confusing part, or which end was up. This issue has never quite been resolved. But many, many clocks ticked. Slowly. With no discernible change in attitudes, although the soft grunting sounds continued, off to one side.

In fact only two sounds were heard - a soft, baffled grunting set against a background of barely heard and extremely slow, possibly imaginary clock ticks.

Hikers were used to unslinging their packs and dropping them into the mud. Nelson's newfangled wooden frame kept the pack off the ground and out of the mud, kept the whole arrangement rigid, and allowed the hiker to lean his pack up against a rock or tree where it would not fall into the mud or even come close to it.

These concepts just could not be grasped.

These concepts were too advanced for the modern world, having been invented a mere five thousand years earlier by guys who wore brain-tanned animal hides and killed supper with a stick. Not quite enough time had elapsed yet for modern man to adapt to these radical ideas.

But Nelson knew he was on to something. It was right. He knew it. He just knew it. It had to be right. If it wasn't right, then why was he lying awake at night mulling it over, for crying out loud? So he kept on. His faith in the Trapper Nelson pack was unbounded. And it was named after him as well, so he had to make it work.

The pack did not sell.

Things did not work out.

Then after several more years the pack continued not selling.

Nelson gave away free samples, mailed out brochures, advertised. Contacted the U.S. Forest Service, Boy Scout troops, famous sportsmen. Left piles of packs in sporting goods shops, on consignment. The thunderous landslide of sudden orders persisted in not arriving all at once, or even slowly over time.

The pack did not sell.

So in 1929 Lloyd Nelson gave up.

"The consensus was that my product was too good-looking for the type of person who carries food, clothes and blankets from place to place," he said. No doubt you yourself have seen some of the descendants of these people. Incomprehensibly, they are too dumb to buy a pack with a frame but not too dumb to breed, which says so much more about evolution than we want to think about.

So Lloyd F. Nelson gave up.

He sold his business to the Trager Manufacturing Company of Seattle, an outfit that had been helping him to manufacture the canvas parts for his pack. Potential customers continued to stare out of glazed eyes in blank incomprehension and scratch lazily while breathing through parted lips.

But not for long.

Because something happened one day.

The mighty universal clock ticked one more tick, and the heavens turned one more degree with an almost inaudible click as the massive hands of that immense clock moved, slightly. Oh, so slightly. Both the little hand and the big one moved, but just a bit. So little you couldn't see anything at all. Nothing much seemed different. Nothing. But the new age had arrived. Suddenly. The earth began to hum in a new sort of way, almost inaudibly, almost imperceptibly. Change was afoot.

Fire season arrived.

Fire season arrived too late for Lloyd Nelson, but not for his pack. His former pack.

Two weeks after Nelson sold out (TWO FRIGGIN WEEKS!) the Forest Service screamed in an order for 500 pack boards, to be delivered pronto. Pronto! "We have a really big fire here!" they screamed. Screamed! Get us some packboards! PRONTO!

This is true. They had this really big, ugly fire to put out, and the pack boards seemed like a good idea, a really good way to carry equipment and supplies back and forth. Yeah, right! Right now! Send them!

They had hundreds of people fighting fires but no packs.

Tick. Two more weeks went by.

Tock. Another order for 500 pack boards came in.

Same deal. More fires. Tick. Things were burning all over. Tock. People were jumping up and down. Pants were on fire everywhere. Suddenly everyone had to have a Trapper Nelson pack. The 20th century came in (a bit behind schedule) riding a bright wave of toasty hot flame.

And Lloyd F. Nelson was hosed.

He missed the fun. All he got was a few bucks for selling out two weeks too soon. He took his two ells and his eff and faded from view, Lloyd F. did. The Trager company continued, and prospered. It continued, supplying outdoor equipment for Eddie Bauer, Recreational Equipment, Inc., L.L. Bean and other companies. Companies like Abercrombie and Fitch. Even Abercrombie and Fitch for a while sold the Trapper Nelson. It was pure, uncut outdoorsy sex appeal, and everyone was crazy to have it. Suddenly, and for a long while after.

Trager was in business for a long while. They later sold mostly smaller items like book bags and so on, to carry the smaller lumpy maybe not quite so useful things that the ultralight backpacker might think of as nonessential. 3

And Lloyd F. Nelson?

Dead. Forgotten.

Almost. Almost forgotten.

– But was that it? –

First the glacier-creeping, fur-capped, arrow-punctured, ditty-bagged, knife-wielding, bow-toting, snowshoe-wearing Frozen Fritz, then a big gap for 5000 years, then (bing!) shiny, Hi-Tek PakBoards™?

Not quite. Equipment started crude and matured slowly. It was mostly homemade. Sometimes it was clever, as with Fritz's grass-stuffed shoes, which Petr Hlavacek, a Czech shoe technologist, and head of the technological laboratory at Tomas Bata University in Zlin, thinks are better than modern footwear.

Zlin. Think about it.

"Wearing the shoes is like going barefoot, only better. They are very comfortable. From a technical point of view they are very strong, sound, and able to protect the wearer's feet against hard ground, extreme temperatures and damp. They also have a very good grip and withstand shock very well", said Petr Hlavacek, after making and testing replicas of Fritz's shoes. In Zlin. 4, 5, 6

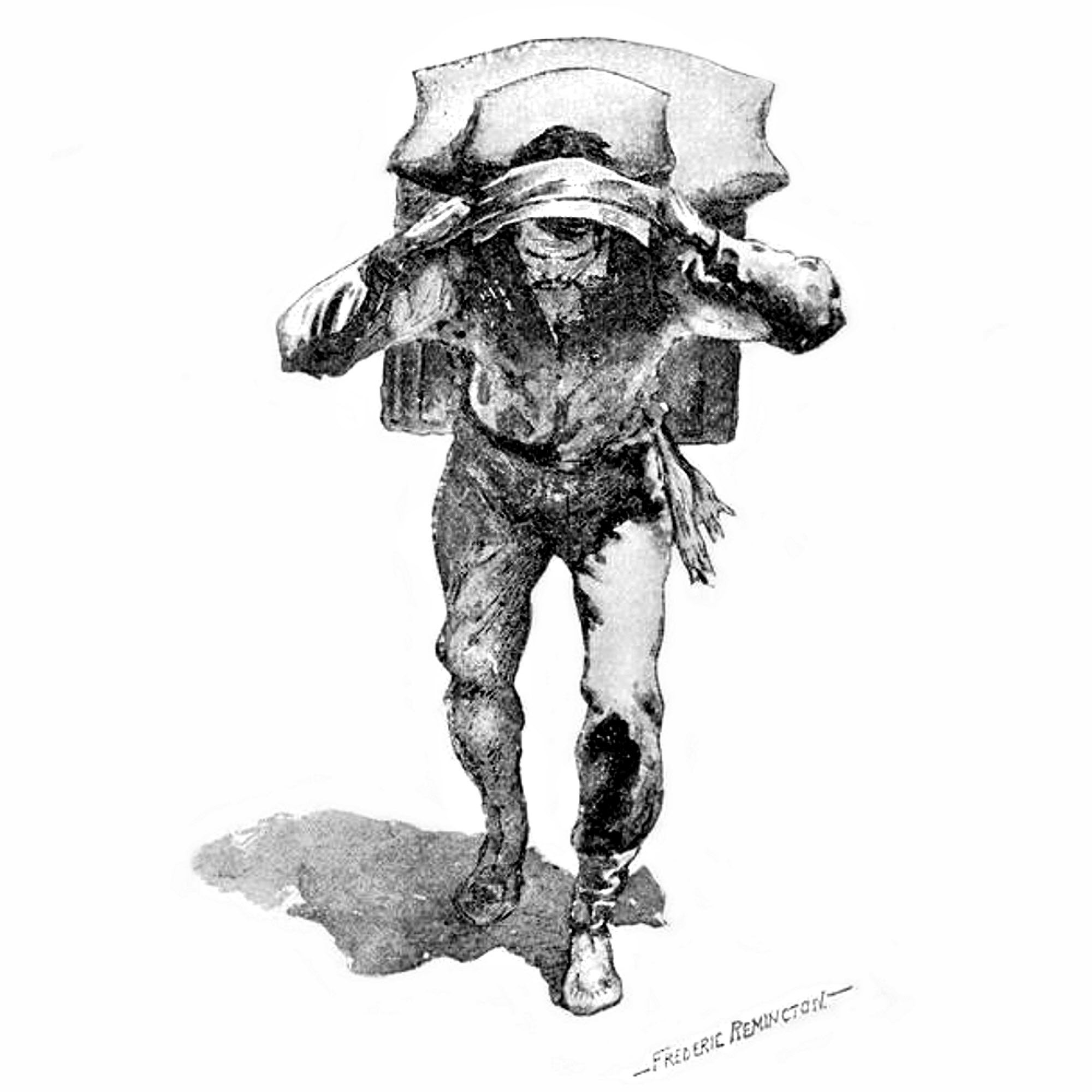

Tumplines were used a lot. "From equatorial jungles to the barrens of the high Arctic, almost every native culture has a form of tumpline. Groups who do not use a tumpline usually represent one of the so-called civilized cultures." 7

First the stick, then the bag, then the tumpline. Easily understood items all. Easily overlooked by someone who thinks cell phones, singles bars, and rush hours are pretty good ideas.

– Tump me mama, tump me. –

(From here to there and back.)

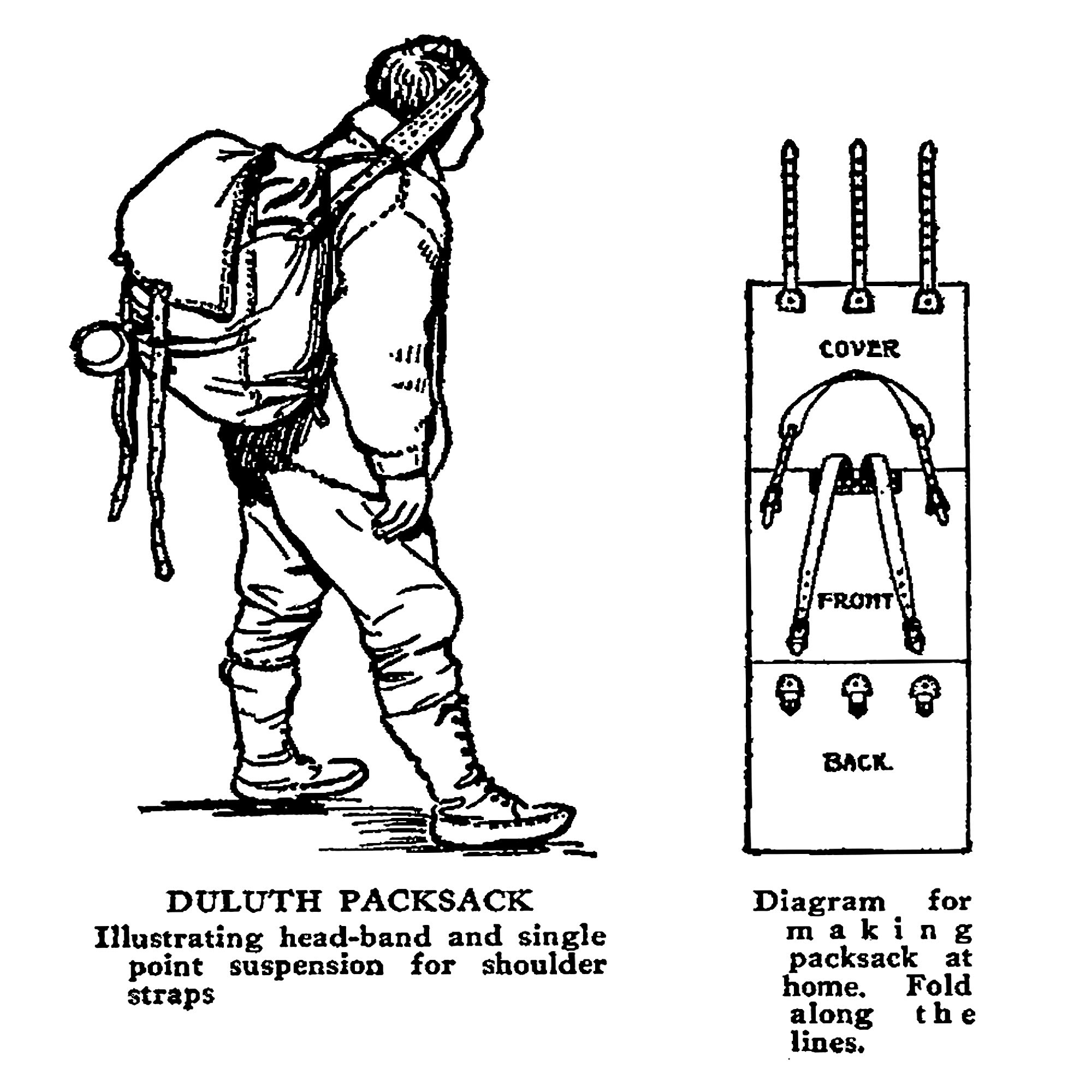

A tumpline isn't a pack, or a bag, or a basket, but it's used with them, like a single shoulder strap that goes over your head instead of your shoulder.

A tumpline has a wide band that rests on the noggin between the forehead and the top of the skull (around the hairline). Toward each lower end the tumpline tapers to a narrow band, which is what attaches to and supports the load. The load in turn is carried in some kind of container close to the back and high up.

The idea is that the hands and arms are free to move, and the load's weight is transferred to the skeleton through the spine. The spine, unlike the body's muscles, is made to carry weight. So this works.

Putting a load up near the shoulders also brings the weight more in line with the body's center of balance, so less energy is needed to carry that weight, a fact that the U.S. Army has confirmed in tests. Go Army!

During the fur trade days of the early 19th century, voyageurs (the canoe paddling human pack animals of the woods and rivers) were normally obliged to simultaneously carry two 90-pound (41 kg) pieces of freight over portages between bodies of water. Using tumplines.

So a man, short and small by today's standards, and weighing around 140 pounds (65 kg), would be carrying at least 180 pounds (82 kg) of cargo. During each carry. And each portage required many carries. Stuff that in your pack and lug it, Bub.

These guys habitually lived on cornmeal mush with a rare piece of salt pork thrown their way as a treat. No, they weren't crazy fit macrobiotic mush nuts. This was all they were allowed. Capitalism, remember that? Bottom line. Profit and loss. Lean and mean - all that. The way it worked in the olden days.

So where are we today? Conover says in his book From Beyond the Paddle that "at the summer games in the Cree village of Mistassini, Quebec, women have carried close to 900 pounds and men have exceeded 1200," over a round-trip route covering 80 feet. With tumplines. (408 kg, 544 kg, and 24 m, respectively.)

Who's a pansy now?

And yes, you saw the right number of zeroes on those numbers. Try thinking primitive technology. Just try.

The Métis Voyageur Games, sponsored by the Manitoba Métis Cultural Club in Winnipeg include a 540 Pound Sack Carry. The rules are: "This carry consists of four, 100 pound sacks with a tumpline, and two, 70 pound sacks saddled over the top sack. Departing the loading platform, the competitor must carry this weight to the farthest distance they possibly can." Before exploding.

Note the team size there: One.

Imagine 540 pounds in your pack. (Let's see...540 pounds divided by 2.2 equals, ah, 245 kg. Damn. You're a big eater then?)

Another game has a 180 pound limit, and is open to both men and women. There are two categories.

The first category is distance. Each sex carries a 180 pound (82 kg) load, but the women's route is a tad shorter. Their route has milestones at 100, 200, and 300 yards (just-about-meters) while the men have milestones at 200, 400, and 600. Medals are awarded to anyone who reaches any milestone whatsoever, with the most prestigious medals going to those who make it all the way. In other words, this is a competition only against death and destruction, with the winners being those still standing among the living.

You win if you do it, and if you also do not die. Either one works.

But wait! There's more!

The second category is speed. The speed games cover a course of 100 yards (91 m) and involve a 90 pound (41 kg) weight. Apparently anyone can compete against anyone else, and the quickest one wins (or dies trying, which is automatically second place at best, if not lower). 8

Conover cites G. Heberton Evans's book Canoeing Wilderness Water, which says of tumplines that "properly adjusted, the device rests on the nice thick frontal portion of the skull and by its very nature lines up all the vertebrae and relies on the long bones of the legs to support the load. A slight forward lean puts all the forces in line with the skeleton, which supports most of the weight. This leaves a person's musculature free to engage in a springy stride that allows for both shock absorption and forward motion. Although the tumpline itself may weigh only a few ounces, it allows the carrying of phenomenal loads that beggar one's sense of credibility."

Beggar. As we've seen. You betcha there.

Today tumplines are used mostly among canoeists, and by only a few of them. Of those who know of it at all, some of them shun the tumpline, some never catch on, and a handful never travel without one. Tumplines made the use of the wanigan possible.

Say what? Wanigan? What be then this wanigan thing?

The wanigan is a handy wooden storage box that fits neatly inside a canoe. It is canoe luggage. Or custom cabinets for your tiny boat. But goofy to carry without a tumpline.

Another modern use of tumplines is to carry pack baskets. These are baskets traditionally woven of black ash withes and still used (but rarely) in the northeastern states. Pack baskets are made mostly by the Micmac, Penobscot, and Passamaquoddy Indians, and are light, rigid, strong, and resilient, though the genuine article is now very expensive.

Tumplines, to be useful, must be precisely adjusted, down to the fraction of an inch (millimeters, my friend). If the tumpline is too tight, the user's head and neck are pulled back and the neck muscles are forced to support the load instead of the spine. If the tumpline is too loose the load rides low on the back and digs in, especially if that load is in a rigid, box-like wanigan.

Despite the possibility of carrying huge weights, accidental falls may be less threatening with a tumpline than with a pack, even if one is carrying a hard-sided wanigan. Falling with a pack means going down with it, because the two of you are strapped into a tight, deadly embrace.

Falling with a tumpline means you can shuck off the load before you hit the deck, and so maybe you do not fall at all. The technique is to dip your head and roll your body to one side to deliberately dump the load in a controlled way, and then regain your balance once you are free of the weight. Only the load ends up on the rocks, and not you. (Garrett Conover)

Ötzi may not have had a tumpline with him the day he died, but he knew about them.

He had to.

They go way, way back. Primitive technology, remember.

Still too advanced for most of us.

– Respect your backbone. –

Nessmuk (a.k.a. George Washington Sears) wrote Woodcraft and Camping in 1884 ( http://bit.ly/1ylhUjO ). Of packs he said: "Firstly, the knapsack; as you are apt to carry it a great many miles, it is well to have it right, and easyfitting at the start. Also, it may be remarked that man is a vertebrate animal and ought to respect his backbone. The loaded pack basket on a heavy carry never fails to get in on the most vulnerable knob of the human vertebrae. The knapsack sits easy, and does not chafe. It holds over half a bushel, carries blanketbag, shelter tent, hatchet, dittybag, tinware, fishing tackle, clothes and two days' rations. It weighs, empty, just twelve ounces."

(Hey, this is ultralight territory here, from 1884!)

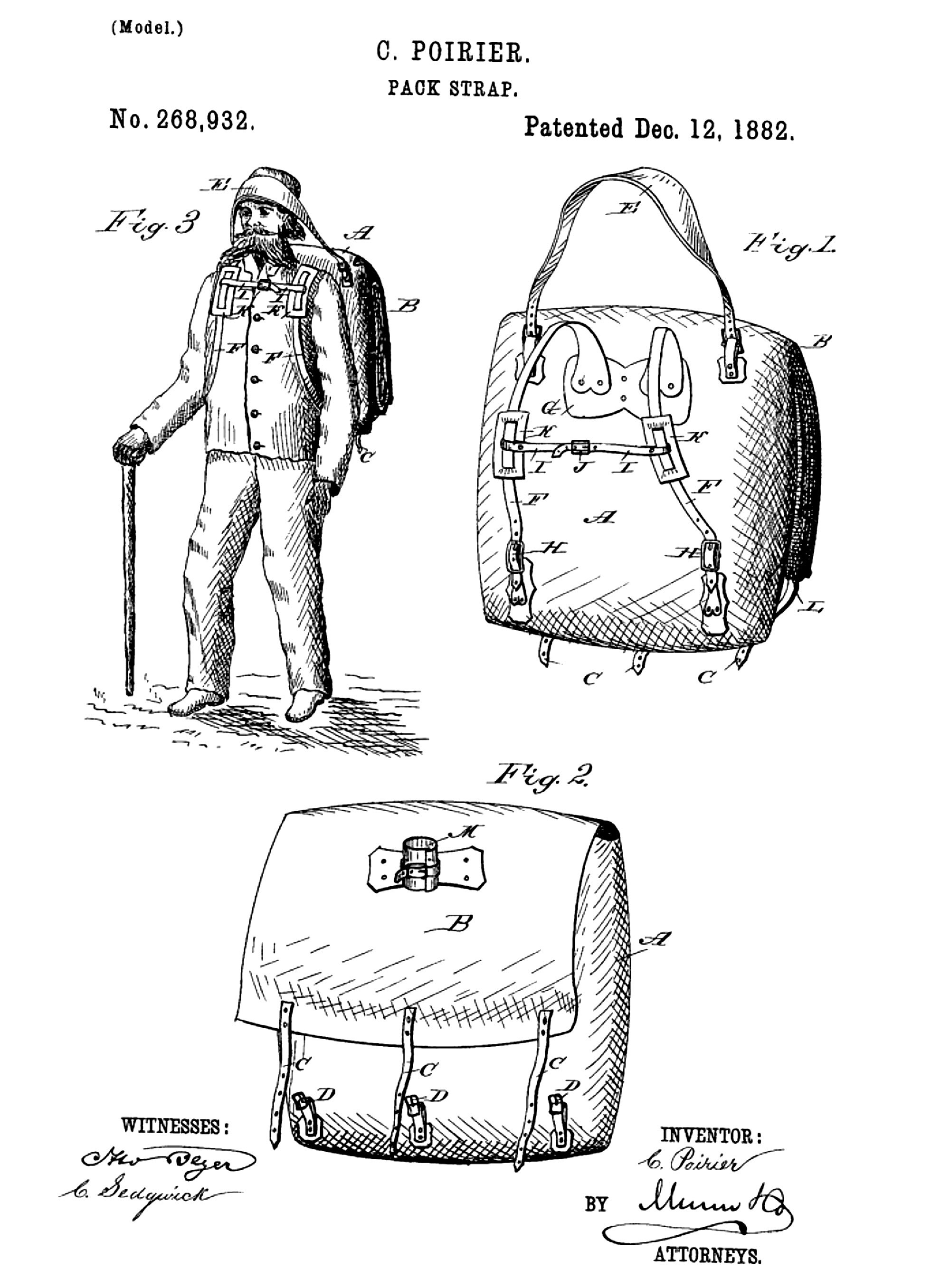

In Nessmuk's day and for a while before, packs were made of leather, or of canvas, which could be waxed or rubberized for waterproofness, or made of oilcloth. There were no hip belts but many of these packs came with tumplines, or a tumpline was easily fitted.

In fact this style of pack, the Duluth Pack is still available through Duluth Pack, of Duluth, Minnesota.

– Camille, I need shoes to go. –

(And a pack with that.)

In 1911 Duluth Tent and Awning bought out Camille Poirier, inventor of and patent holder (1882) on a new kind of pack, "a canvas sack that closed with a buckled flap, had new-fangled shoulder straps in addition to the traditional tumpline, a revolutionary sternum strap and an umbrella holder."

Originally known as the Poirier Pack, this very item lives on as the Duluth Pack, a brand name of Duluth Tent & Awning, a company now known as Duluth Pack.

Poirier was born in 1838 to poor parents in French Canada. He had two years of schooling, between the ages of seven and nine, and at age 14 began work in a shoe shop, putting in 15 hours a day for a salary of $10 a year. After he learned the trade inside out, forward and backward, he got a raise. His pay jumped to $72 a year.

An ax accident partly crippled him while he was trying out life in England, and despite his best efforts he remained poor, so it was first back to Canada, and then to St. Paul, Minnesota. "When I left Canada I was working 12 hours a day at 75 cents and I was a fast workman, I got two and three dollars a day in St. Paul I tell you I was greatly surprise."

(Just to be absolutely clear, when he said "12 hours a day at 75 cents and I was a fast workman", he meant that he, as an expert, worked 12 hours a day for a total of 75 cents for the day. Not 75 cents an hour. Think long and hard about that one.)

Rising to the position of foreman of a large shoe shop in St. Paul at $1000 a year still wasn't enough though.

The idea of running his own business led Poirier to Duluth. He found sleeping space on the floor of a boarding house for $7 a week, meals included: "What struck me was a big pile of green wood 10 to 12 feet long right at the front of the door and the carcase of a cow or bull on top of it the cook would go out with an axe and chop good chunks of the frozen meat and that was our bouillion lots of onions and Duluth soil mixed in place of pepper."

With savings he had brought with him to Duluth, Poirier built a workshop and home, and soon had six employees, and steady money coming in, so early in the spring of 1871 it was time to send for the wife and kids. "I bought my wife proud as a king to our new mansion the frost was covering the walls 1/2" inch thick in the morning, but bread frozen solid and every thing the same way."

Later, shortly after dropping his expensive fire insurance he was burned out, losing everything, and falling $15,000 behind. And remember, that wasn't $15,000 in today's money. Add a few zeros on the end to cover the conversion factor.

It was a staggering loss.

But Poirier persevered and recovered, relying on the patience of his creditors. Later he moved into "a cement house store and home." Business went well but he still worked hard. "I opened the store at six and keep open from eleven to twelve every night and Sunday was a good day I would go up to my Sunday dinner and some body would ring the bell and had to go down again." A mere seven-day workweek.

Then another fire. A nearby building caught, then a barrel of kerosene rolled down the street and exploded in front of his shop. A $40,000 loss this time. Time to start over again. Later "Henry Bell offered me $30,000.00 cash for the building and I was tired of the business and I thought I was rich and I took it. I then went in speculating bargins on property twenty years to soon...when 94 came I went down like a rock."

At age 56 Camille Poirier had to start over yet again.

At age 56 Camille Poirier was an old man.

In those days you either did it or died. If you couldn't work you couldn't eat.

Poirier had nothing but debt, his skilled fingers, good business sense, and a reputation. They were barely enough to keep him and his family alive. Barely.

Feeling old he nevertheless remained cheerful and kept at it, glad at least to have three meals a day. A few years later, in 1911, he was able to sell out to Duluth Tent & Awning and pass along his innovations to us backpackers, who really have it pretty easy, except for the dirt in our food. We still have that. ( http://bit.ly/1bjq9Bg )

Duluth Pack has now been in business almost 130 years. Its 2006 earnings were $5 million. "Workers hand-cut and stitch every piece of canvas and leather that goes into its products. Even riveting operations aren't mechanized, with the company opting instead for experienced craftsmen wielding ball-peen hammers. All this work takes place inside the original storefront Duluth Tent & Awning first occupied at 1610 W. Superior St. in 1911." 10, 11

If Mr Poirier could visit today he would see it, and know it, and understand it, and be proud.

Wouldn't you?

– Footsie Notes –

1: Ötzi the Iceman from The Humanities Program: http://bit.ly/14RbefO See also: Iceman: Uncovering the life and times of a prehistoric man found in an Alpine glacier, by Brenda Fowler ISBN: 0679431675, 330 pages, University of Chicago Press, 2001 And: The Man in the Ice: The discovery of a 5,000-year-old body reveals the secrets of the stone age, by Konrad Spindler ISBN: 0517799693, 305 pages, Harmony Books, 1995

2: Blood on the axe from New Scientist archives: http://bit.ly/1aAQ6cN

3: A Brief History of How Backpacking Got It's Name [sic] from Trager (now defunct): http://bit.ly/1D09IZ8

4: Ötzi's Shoes from The Engines of Our Ingenuity, University of Houston: http://bit.ly/15tWHVJ

5: Hay Beats GORE-TEX from Science Magazine, American Association for the Advancement of Science. Try http://bit.ly/2iJjtqR or http://bit.ly/2kaejom (Access has been limited to a sample of the original article.)

6: Shoemaker pursues the ultimate sole mate from The Sydney Morning Herald: http://bit.ly/17zW9NE

7: Garrett Conover, Beyond the Paddle: A Canoeist's Guide to Expedition Skills-Polling, Lining, Portaging, and Maneuvering Through Ice, 1991, isbn 0884480666

8: Voyageur Games 540 Pound Sack Carry from Métis Nation of Ontario: http://bit.ly/161ll2A

9: Autobiography of Camille Poirier from Sheldon Aubut's Duluth History: http://bit.ly/1bjq9Bg

10: Duluth Pack is bursting at the seams, 07/23/2007, Duluth News Tribune: http://bit.ly/1vxf7Ne (partial content)

11: About Duluth Pack: http://bit.ly/1zGooH7

12: Original Duluth Pack from Duluth Pack web site: http://bit.ly/1yIKfPR